Where do I begin?

It’s an in-joke that composer Howard Goodall could hardly pass by – quoting that song in his and Stephen Clark’s musical adaptation of the much-loved novel and film LOVE STORY. But it’s the moment he chooses that raises wry smiles from us all. It’s Jenny Cavilleri’s much-anticipated Bach recital and there it is, the schmaltziest of songs dressed up in the most elegant of garbs – all Bachian passage work and filigree. But that’s the kind of unlaboured wit and charm that raises Love Story above the norm – because Goodall, one of our most conspicuously gifted notesmiths, is so musically literate that nothing is there by chance, nothing is superfluous.

I’ve always believed that Goodall had a great musical in him – one might argue that he has already written it with The Hired Man (a homespun masterpiece if ever there was one) – and although Love Story is probably not it, there is a feeling when you leave the theatre that you have been touched by something as elegant as it is unpretentious. How easy it would be to over-egg this one, to lay on the power ballads of love and loss and in so doing destroy the intimacy and pacy wit of Erich Segal’s original.

Stephen Clark does a good job of replicating that in his book and Rachel Kavanaugh’s direction mirrors it in the fluent minimalist staging and although Clark is no Sondheim his song lyrics are at least plain spoken in the same honest voice as his dialogue. And there are flashes of brilliance – most notably the “pasta song” which reels out the entire assortment of pasta types is a flurry of cheesy (parmigiano, of course) rhymes. But again it is Goodall who nails it with the catchiest of hooks opening out the melody in long notes just as you expect to be bouncing along with the shorter and pithier variety.

Goodall’s lovely score feels organic, partly because he has orchestrated it himself for a distinctive “Ivy League” combination of piano, string quintet, and guitar, and partly, no especially, because he understands the subliminal way in which the emotional memory of melody works. His tunes are discreetly memorable and he and Clark have found ways of reprising them in whole or part so that a simple change of word can emotionally wrong foot us. Best of all, singing here feels like a natural extension of speech – the “same voice” syndrome – so that you feel comfortable with the convention. It helps that the music is so beautifully sung – not least by the delectable and touching Emma Williams but also by her co-star Michael Xavier who has the trickier task of conveying the debilitating emotional inhibitions he might or might not have inherited from his parents and doing so in a high vocal tessitura. And let’s not forget Peter Polycarpou whose big-hearted awkwardness as Jenny’s widower father Phil is so gently and amusingly conveyed every time he’s on stage. He’s already watched Jenny’s mother die and the idea of her being there in spirit as history repeats itself is a nice touch – though, of course, the big questions remain unanswerable.

Love Story works because it’s honest and subtle and always avoids grandstanding the sentimentality. It’s an unlikely success that I know will repay familiarity. Indeed it could well be the surprise sleeper that the West End needs right now – a small show with a really big heart.

You May Also Like

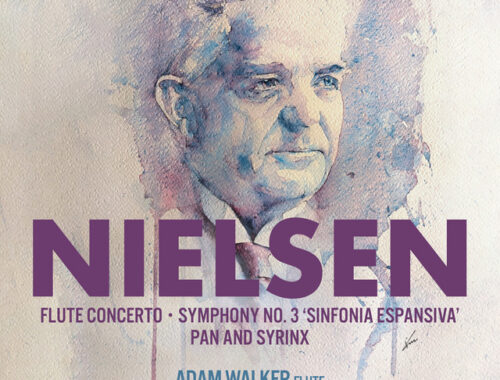

GRAMOPHONE Review: NIELSEN Flute Concerto, Symphony No. 3, Pan & Syrinx – Bergen Philharmonic/Gardner

03/06/2024

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – July 2020

22/07/2020