Titanic, Southwark Playhouse (Review)

In years to come we’ll look back on the shrinking (as opposed to sinking) of Titanic as the moment that the heart and soul of Maury Yeston and Peter Stone’s musical epic at last found and touched its audience. Like the reduction of a fine culinary sauce the flavours of Titanic – the musical are intensified in the process – we are closer to the people and subsequently closer to the essence of Yeston and Stone’s musical drama when the cast of thousands numbers 20 and the sheer scale of “the largest moving object in the world” is entirely in our collective imaginations. Thom Southerland’s incisive and exciting staging at the new Southwark Playhouse opens our hearts and minds to the dreams and aspirations of an entire age – the Industrial Revolution – and through ingenious sleight of hand and economy of means – which actually Yeston and Stone’s piece has in spades – finally reveals what a terrific musical it is.

In years to come we’ll look back on the shrinking (as opposed to sinking) of Titanic as the moment that the heart and soul of Maury Yeston and Peter Stone’s musical epic at last found and touched its audience. Like the reduction of a fine culinary sauce the flavours of Titanic – the musical are intensified in the process – we are closer to the people and subsequently closer to the essence of Yeston and Stone’s musical drama when the cast of thousands numbers 20 and the sheer scale of “the largest moving object in the world” is entirely in our collective imaginations. Thom Southerland’s incisive and exciting staging at the new Southwark Playhouse opens our hearts and minds to the dreams and aspirations of an entire age – the Industrial Revolution – and through ingenious sleight of hand and economy of means – which actually Yeston and Stone’s piece has in spades – finally reveals what a terrific musical it is.

As opening numbers go Titanic is up there with Flaherty and Ahrens‘ Ragtime and Bock and Harnick’s The Rothschilds as one of the great set-ups in musical theatre history. An unbroken 10-minute plus sequence. The ship’s designer Thomas Andrews (Greg Castiglioni) is poring over the blueprints as we take our seats and in premonition of impending disaster Southerland has Simon Green’s excellent J. Bruce Ismay, the ship’s owner, besieged by an angry mob, his eventual survival an affront to the many souls lost in part to his recklessness and ambition. Already there is a mighty drama brewing and once boarding starts the musical motifs start to soar in harmony with the mind-boggling statistics. Titanic and all who sail in her constitutes a floating kingdom and we don’t need to see it to believe it. That’s what theatre can do. Yeston goes all out for the aspirational now and the climactic hymn “Godspeed Titanic”, replete with thrilling harmonic suspensions, is uplifting in the extreme in this intimate space.

Designer David Woodhead has implied scale with a wall of steel and a simple split-level prospect. The vaulted ceiling of the Playhouse is in itself ship-like – a kind of inverted hull – while a moving stairway is every vantage point, not least, of course, the crow’s nest where an astonished nightwatchman first spies the mountainous iceberg. A marvelous act one curtain, this, as Yeston’s hypnotic number “No Moon” has lulled us into a false sense of security – the eerie calm before catastrophe.

For me the evening’s greatest revelation was perhaps its greatest deception – Ian Weinberger’s masterful orchestrations for a mere six pieces. As one who cherishes this score for the richness of its characterisation I was astonished how completely it was served by essentially a string quartet (with double-bass), keyboard (MD Mark Aspinall), and percussion. All the resonance one might have thought would be lacking was there in abundance while the warmth of a string centre made for all the intimacy and old-worldly charm one could wish for. For my money the score, with all its myriad allusions to the music of this our sceptered isle, sounded more sheerly gorgeous than it did originally with a 28-piece band.

A smashing and ultimately very moving evening, then, achieved with minimal means and maximum heart. I won’t reveal how Southerland and his designer depict the ship’s final moments but they unlock the horror in our imaginations with the simplest of effects and in the aftermath of the tragedy, when we learn at last the terrible facts from the mouths of survivors, Southerland brings back the departed to mingle with the living, the former quite literally, ritualistically, bowing out of the proceedings with quiet dignity.

This is an ensemble show in every sense, especially when multi-cast as effectively as it is here, but, of course, there are stand-out performances – from Celia Graham’s Alice Beane, who so wants to dance “with the first class”, from Dudley Rogers and Judith Street as Isidor and Ida Strauss whose 40 years of marriage have made them inseparable (how touching their song “Still” is), and from James Austen-Murray whose stoker Barrett is physically, vocally, so virile.

And that brings me to the most precious of Maury Yeston’s inspirations in this score – the juxtaposition of the numbers “The Proposal/The Night was Alive” where Barrett persuades the telegraph operator, Bride (Matthew Crowe) to transmit his proposal of marriage to his sweetheart in Ireland and one young man’s ardent expression of love is heard and felt in the context of a world of connections being made through the ether of the night. It’s a glorious number and it does what only musical theatre can do.

Yeston was in the audience on opening night mouthing every lyric, silent humming every tune. He looked proud as well he might.

Photo: TITANIC at the Southwark Playhouse

Credit: Annabel Vere

A Conversation With MAURY YESTON

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – January 2019

30/01/2019

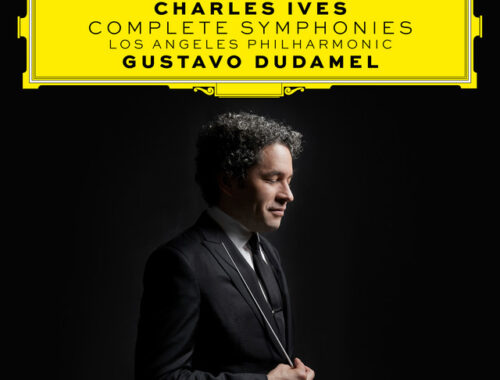

GRAMOPHONE Review: Ives Complete Symphonies – Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra/Dudamel

07/10/2020