St Petersburg Philharmonic, Vengerov, Temirkanov, Barbican Hall

When you are arguably the greatest violinist in the world a four-year “time out” from the public arena can seem like an eternity. But it’s a time for renewal, too, and though absence makes audiences’ hearts grow fonder (and nowhere more so than in London), expectations grow higher, too. Which is perhaps why – on the stage of some of his greatest triumphs: Barbican Hall – Maxim Vengerov slipped a shade uneasily into the opening measures of Prokofiev’s First Violin Concerto. This is such stuff as dreams are made of but where one has come to expect the ravishing solo line to hang suspended on the threshold of its own fine-spun fantasy Vengerov was impatient to move it on – almost as if making up for lost time.

The sound was burnished and rapturous, of course, but the rubato kept pushing at the stability of the tempi and there were moments throughout the first two movements where Vengerov uncharacteristically threatened to run away from or even break free of the St Petersburg Philharmonic. Yuri Temirkanov needed his wits about him. The solo flute poetically returned calm with Vengerov at last easing into his ecstatic embroidery.

No such uncertainty about the parodistic aspects of the piece. Vengerov was a demented hornet in the central scherzo with trenchant quavers reiterated sul ponticello (on the bridge) to scarifying effect. Likewise in the finale where a restless night turns into a transfigured one. Vengerov lives in those high positions on the E string and as his fluttery trills vapourised at the close we transfixed once more by his genius. A Bach Sarabande restored nobility and voiced double-stopping to some sort of perfection. He has been missed.

A deep and rosiny string unison launched Shostakovich’s 7th Symphony “Leningrad” with Temirkanov maintaining his somewhat benign demeanour even as one of the great mutations in music made something monstrous of that irritating and seemingly innocuous tune in the first movement. Stalin’s foot-tapping turned to jackboots.

The playing was a little rough and ready – or should that be “home spun” – in places but star performances emerged in poetic piccolo and bassoon solos and the great heart of the piece – that extraordinary slow movement – projected the pain of a great nation in its stark string recitatives. But beyond the pain was bursting pride and as the songful opening unison returned in triumphant brass at the close the irony of the St Petersburg Philharmonic playing the Leningrad Symphony was inescapable.

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – July 2018

17/07/2018

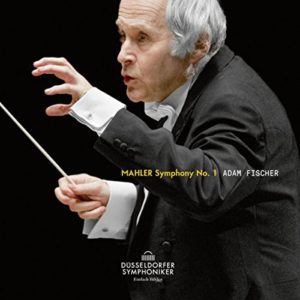

GRAMOPHONE Review: Mahler Symphony No. 1 – Düsseldorfer Symphoniker / Fischer

24/04/2018