Risor Festival of Chamber Music at Wigmore Hall

Each year, Risor – a small fishing town on the south-eastern coast of Norway – hosts an internationally renowned festival of chamber music. This week some of its key players decamped to Wigmore Hall and naturally they brought a little piece of Norway with them. Violinist Henning Kraggerud and pianist Marc-André Hamerlin opened proceedings with the first of Grieg’s violin sonatas – in F major – and for half an hour or so Norway’s most famous son did a very passable impression of Brahms.

The tunes, of course, have their own folksy cast, not least a lovely idea in the finale which is led off by the piano and echoed in the violin, but the tone – for all its attempts at a Handanger fiddle imitation in the communal sing-song of the scherzo – is decidedly Brahmsian and even momentarily (for those Brits in attendance) Elgarian. It was most generously played by the talented Kraggerud – songful and “swung”.

Clear fresh air and an almost naïve openness then seemed to evaporate as the hall became a hothouse for a sequence of high-flown and sensuous songs by Liszt, Wagner, Brahms, Duparc and Chausson. The singer was Measha Brueggergosman – and it quickly became apparent that all was not well with this voice. The distinctive mezzo colour which she once carried through the entire range seems to have separated and grown remote from it. The middle is shallow, lacking body and resonance, and the top has become shrill and pushed. She’s always been a very spiritual, feeling, kind of singer but her “connection” with text did not on this occasion extend to the distinctive colour of the French and German. Wagner’s “study for Tristan und Isolde” “Im Treibhaus” was distressingly diminished by her closed sound and short-winded phrasing.

But four or more stars beckoned as Festival co-director Leif Ove Andsnes and colleagues Kraggerud, Lars Anders Tomter, and Torleif Thedéen lustily tapped into the gypsy in all our souls and turned in a performance of the Brahms Piano Quartet in G minor that made one wonder why Schoenberg ever bothered to orchestrate it. Those sumptuous unisons from violin and viola, violin and cello, the schmaltz and swagger and sweep of it all was irresistibly rangy. Andsnes was positively orchestral in the depth of his sound, his right hand faster than the speed of light in suggesting the cimbalom rattling through the Rondo finale’s knees-up. Terrific.

LPO/ Petrenko, Royal Festival Hall

You May Also Like

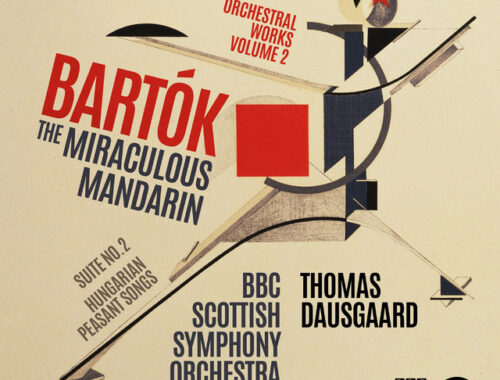

GRAMOPHONE Review: Bartók Orchestral Works, Vol 2 – BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra/Dausgaard

19/05/2021

TALKING POINT: TRACIE BENNETT in conversation with Edward Seckerson

15/01/2025