Puccini “Madama Butterfly”, Royal Opera House

One can only hope that the ill wind which strips away the cherry blossom at the close of Patrice Caurier and Moshe Leiser’s feeble 2003 production of Madama Butterfly might soon carry off the entire staging. I’ve seen some cheesy operatic moments over the years but the sight of poor Butterfly in her death throes fluttering her kimono sleeves like a… well, go figure… is up there with the cheesiest. Puccini deserves better, audiences deserve better, and if the best a director (leave alone a pair of directors) can come up with is the tired old dead-butterfly-pinned-to-a-board metaphor (even Puccini and his librettists struggle with that) then we really are in trouble.

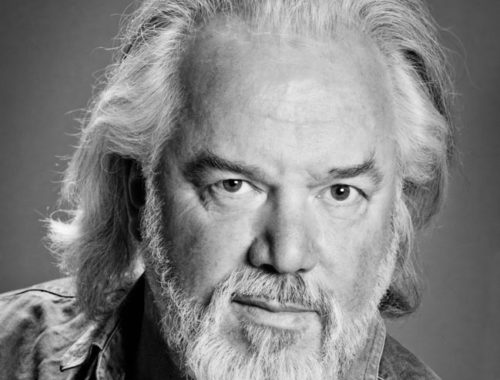

We are in trouble, too, if that cad Pinkerton is cast for his height and not his heroics. That the exceptionally tall and lithe James Valenti really is American hardly qualifies him for a role that is far beyond what his elegant voice can deliver. One appreciates the tender touch, the attempts at finessing and beguiling Pinkerton’s sweet nothings, but the top needs to be big and arrogant in this role and if the high Bs and crucial C don’t carry or sound, as here, like they are being cheated in falsetto then looking the part is neither here nor there.

Anthony Michaels-Moore looks and sounds the part as the US Consul Sharpless but the act one duet with Pinkerton is hardly even handed. And not does the conductor Andris Nelsons take any prisoners in the big-sell moments. His is a wonderfully rhythmic, flamboyant reading of the score, full of verve and vigour but it also plays to great effect on the fragility and delicacy of Puccini’s Japanoiserie. The Royal Opera Orchestra rise to him: the moment of Butterfly’s premature euphoria at Pinkerton’s return is thrillingly full-on expressing in sound everything that Butterfly cannot convey in words.

The three-star rating cannot do justice to him nor that of the evening’s real star turn. Catch if you can Kristine Opolais’ remaining two performances in the title role because she really is the business. Her transition from quietly shy and seductive, the voice fluttering through endlessly melting portamenti, to womanly resolve and ultimate heartbreak is tremendous. She moves like a figment of our imagination and in “One Fine Day” her storytelling is uncommonly vivid, the plangent middle voice lifted to ecstasy in the climactic and defiant high B-flat. She deserves better than the indignity of those final moments.