Prom 75: Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Haitink, Royal Albert Hall – Review ****

The Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra can play Haydn’s last symphony – No 104 “London” – in its sleep but that is not, I hasten to add, the impression one wants to take away from any performance of it and especially not in the city that inspired it. The music tells us that Haydn had a rather better time in our capital than Bernard Haitink would have us believe but this rather dogged account on the penultimate night of the Prom season seemed to suppress the work’s genial good humour and pre-empt most of its surprises with a one-size-fits-all approach. Haydn was many things – dull was not one of them.

Part of the problem was the strictness of Haitink’s time-beating and the plumpness of the sound where from my seat in the rear sector of the stalls a heaviness pervaded with rhythm and articulation not as sharply defined as one is now accustomed to in our stylistically aware times. The pomp and circumstance was there (albeit a night early) but what didn’t register in any way, shape, or form was the music’s charm. Affection, too, was at a premium and time and again – and I’m thinking particularly of the violins‘ gorgeous little ritornello-like phrase in the slow movement – one so wanted Haitink to give way and allow a little more room for these players to savour what comes so naturally to them.

Haitink returned only once to acknowledge the generously protracted applause. He was no doubt conserving his energy: he had a mountain to climb – or, to be more precise, Strauss’ Alpine Symphony. We were now well and truly in the foothills of Vienna Philharmonic heaven and as the trombones sounded their first intimation of the splendours that lay in wait above, all that was required of the venerable and venerated maestro was a very real sense of this music finding its own space. He delivered. And as the early morning mists cleared in preparation for Strauss‘ thrilling “reveal” those fabled Vienna violins soared and nine horns (with that characteristic wide-bore sound) opened up the first of many fabulous vistas.

Up through the canyons we went with the distant sound of London Brass providing only two short of the 12 offstage horns specified by Strauss. The first glimpse of alpine waterfalls (Strauss working wonders with torrential high violins, piccolos, and glockenspiel) was astonishing and at the summit the passage Strauss called simply “Vision” had the VPO’s intrepid first trumpet nailing the first of many stratospheric bullseyes and the Albert Hall’s mighty organ buttressing the sound from below. I’m still wondering how adjustments were made to deploy the organ when this orchestra is one of a select few playing at a notably higher pitch. One recalls a number of Proms where an electronic job was brought in for just this reason.

Special effects abound in Alpine Symphony and the wind machine went into overdrive as the mother of all storms disrupted the descent. The climactic quadruple-forte with two thunder sheets shaken, rattled, and rolled was pretty stupendous. But this piece isn’t entirely about technicoloured spectacle and as the philosophical apotheosis arrived with all its pantheistic overtones in praise of man’s relationship with nature this orchestra and conductor assumed ownership of it and shared a level of profundity that it so rarely achieves.

You May Also Like

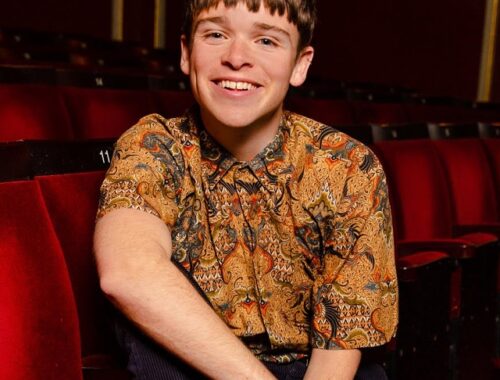

Edward Seckerson meets JAMIE PARKER

17/05/2023

COMPARING NOTES WITH LEWIS CORNAY

20/04/2021