Prom 58: Mendelssohn “Elijah”, Gabireli Consort & Players, McCreesh, Royal Albert Hall

When the fiery chariot finally arrived to transport Elijah aloft and the antiphonal trumpets and drums and assorted ophicleides of Paul McCreesh’s mightily augmented Gabrieli Players Consort and Players were rent asunder by the open-stopped thrust of the Royal Albert Hall organ you suddenly realised why the Victorians became damp with ecstasy at the very mention of the prophet’s name.

Mendelssohn celebrated oratorio has long been at the top of the oratorio heap, beloved by choral societies up and down the land. As communal “sings” go, this one redefines the phrase full-throated and lends every conceivable opportunity for a choir or choirs to strut their stuff in numbers which run the gamut from Old Testament sternness to joyful affirmation. Fielding a Mahlerian sized orchestra full of period touches – like the aforementioned ophicleides (a kind of big vertical bugle) and a trio of serpents (distant ancestor of the tuba) – and a clutch of youth choirs buttressing the Wroclaw Philharmonic Choir, Paul McCreesh went all-out for the full Victorian monty in a hall (and a festival) which demanded nothing less – and from the moment that that startling cry of “Help, Lord!” went up from The People to rattle the Albert Hall’s acoustic discs those of a nervous disposition were given fair warning.

But “Victorian” though this performance was in scale and period detail its vitality and uplift had nothing whatever to do with the kind of Teutonic dead weight that the piece has acquired over the years. The wonder here was that so many voices could so cleanly articulate the exuberance of Mendelssohn’s choral writing. Familiar choruses like “Thanks be to God!” at the close of part one or “Be not afraid” at the start of part two, boasting pneumatic organ pedal work, were not just rousing in the best sense of the word but airy – a seeming contradiction of lightness and heft held in perfect accord.

There is, of course, wonderful textural variety in the piece with quartets and solo numbers making for intimate “asides” from the big gestures. And those tunes – each with a kind of Sullivanesque catchiness in the hook but blessed with Mendelssohnian discretion. Rosemary Joshua, Sarah Connolly, Robert Murray, and Simon Keenlyside all seized their moments in the light but it was the way that that light collectively shone forth that made this a night to remember.

You May Also Like

A Conversation With MICHAEL BALL

02/09/2010

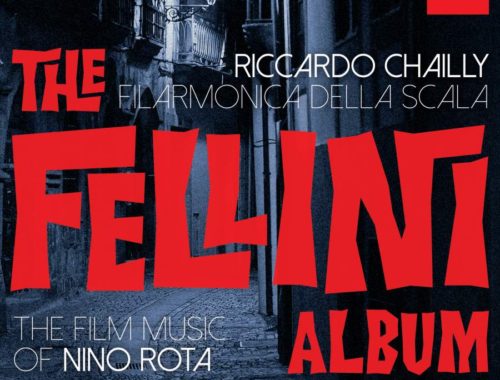

GRAMOPHONE Review: The Fellini Album – The Film Music of Nino Rota, Filarmonica Della Scala/Chailly

14/08/2019