Prom 52: London Symphony Orchestra, Gergiev, Royal Albert Hall

Two Prokofiev symphonies for the price of one – the First and Fifth, the little and large of the canon – and surprisingly it was the bantam weight First that yielded Valery Gergiev’s biggest surprises and tiniest revelations. Rarely has it sounded so tantalisingly Haydnesque.

By no stretch of the imagination could you have described Gergiev’s tempo for the opening movement as Allegro – its deliberation bordered on cumbersome. But impetus came through the clarity of the inner parts – the piquancy and personality of the woodwinds, the deftness of the articulation. Prokofiev’s quirkiness bows to the twinkle in Papa Haydn’s eye as airy violins flick out a minuet with clumsy bassoons marking time. “Classical” inflections, romantic temperament. High lying violins seemed literally to float the exquisite Larghetto while the chortling finale was racy and then some. Suddenly the deliberation of Gergiev’s opening movement made sense.

The evening’s concerto went by another name – L’abre des songes – in which the composer Henri Dutilleux fashioned a notional tree of mélodies proliferating like new growth through all the seasons of our existence. This exotic confection reeks of Frenchness, its shimmer and swagger demonstrative of a wonderfully sharp ear and composerly imagination. The tart twang of the cimbalom is the citrus to the violin’s sweetness, tuned percussion lends light-catching brilliance, and all the while the soloist spins his songful fantasy. What could be lovelier than the central duet for violin and oboe d’amore, its heady enchantment making perfume of sound. The ever-accomplished Leonidas Kavakos became a latterday troubadour, his virtuosity worn with customary modesty.

The evening’s big number – Prokofiev’s 5th Symphony – was prefaced by a Dutilleux fanfare and a Prom premiere: a little something he wrote for Mstislav Rostropovich back in 1977. Arriving with a flourish and exiting with a squeak, Slava’s Fanfare encapsulates something of the grandiosity and mordant humour of the symphony. Gergiev knows how that goes as surely as did Slava before him and with the London Symphony Orchestra on expensive form this was just what the composer ordered.

Gergiev’s instinctive feeling for those “inner rubatos”, the little fluctuations and animations that tantalise and excite, lent authenticity to the brew and from the shiny Cadillac tune in the trio of the scherzo and the shot-silk ravishments of the Romeo and Juliet inflected slow movement to the wacky wood-block driven coda of the finale this was, in a word, epic.

You May Also Like

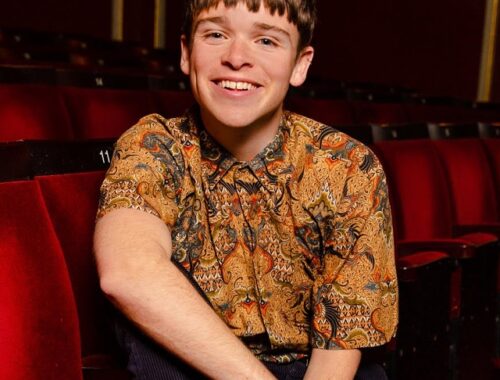

COMPARING NOTES WITH LEWIS CORNAY

20/04/2021

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – December 2019

01/01/2020