Prom 28: BBC Symphony Orchestra, BBC Singers (Men’s voices), BBC Symphony Chorus (Men’s voices), Oramo, Royal Albert Hall

All kinds of narratives at play in this Sakari Oramo/ BBC Symphony Orchestra Prom – and perhaps the truly adventurous programmer might have double-deployed Rory Kinnear – dispassionately chronicling Stravinsky’s Oedipus rex – and taken us beyond the Overture and into the melodramas of Beethoven’s Incidental Music to Egmont. Mind you, that overture will more than suffice as a self-contained drama when it is as boldly drawn as it was here with a daring expansiveness in the lowering F minor Introduction and equally impulsive and defiant allegro with John Chimes’ hard-sticked timpani rattling towards certain victory. The Dutch were bound to prevail over their Spanish overlords with Beethoven in freedom-fighting mode.

But then for something completely different – though it could be argued that Brett Dean’s Electric Preludes for electric violin and strings was incidental music of a kind, too: the kind that might underscore a Hitchcock movie (clear overtones of Bernard Herrmann in swooning Vertigo mode for the final movement) or some lunar adventure. The slow sections of this piece were as much to do with atmosphere as anything else with the amplified soloist – the virtuosic Francesco D’Orazio – thrown into the high relief of a neon-lit protagonist outlining hazy horizons or whistling like Messiaen’s beloved ondes martenot over a fine rain of descending string scales. More effect than music? Perhaps. Though there were thrills and spills in the strenuous work-out sections where the juxtaposition of electronic and acoustic brought dramatic surprises like the sudden descent to earth in the juddering string basses of the second movement while D’Orazio zipped into the ether or the wild cadenza which just for a moment sounded like something Jimi Hendrix might have come up with had he played the electric violin.

The audience swelled somewhat for the evening’s real masterpiece – Stravinsky’s opera-cum-oratorio Oedipus rex – and what a masterpiece it is. No one else could have written it but equally there is nothing else remotely like it – an extraordinary balancing act between the dispassionate and highly emotive, the coolly stylised and highly theatrical, the hieratical and jazzily parodistic. Oramo maintained an intriguing tension between all these elements in tight alliance with his “Greek chorus” of gentlemen from the BBC Singers and BBC Symphony Chorus whose sculpted, chiseled, or vigorously hewn choruses were wonderfully “present” in a hall where immediacy is nigh on impossible to achieve.

That’s particularly true of the soloists though in Allan Clayton we had a marvelous Oedipus – stentorian in his tenorial declamations and with a glorious line in lyric/heroic coloratura where Stravinsky’s vocal lines are at their most melismatic and expressive. Marvelous, too, how he found a way of making something transfixing, almost abstract, of his head-voice departures like the line “All is brought to light” where “lux” was eerily literal in its colour.

Then there was the extraordinary Hilary Summers whose showing as Jocasta negotiated the near-impossible register switches and freakish excitement of her big number with great aplomb and clever musicianship. The drama is most certainly in the vocal pyrotechnics – you don’t need to add too much to their histrionics. I loved the plangency and sinuousness of her blue-note bluesiness and my goodness how Stravinsky had soaked up the Gershwinesque Americanisms in his E-flat clarinet writing. Rhapsody in Red.

All the soloists were well cast bar one – the inexplicably dismal Creon of Juha Uusitalo who didn’t manage to land any aspect of his big number and whose pitchiness had to be heard to be believed. Perhaps Brindley Sherratt (Tiresias) should have had a crack at both roles.

The way Rory Kinnear (Speaker) eased us from the casually conversational to the crisply rhetorical in his opening address set the tone for the whole performance. The wail of chorus and orchestra in the opening music conveyed the sense of huge emotions constrained by judicious objectivity – and when at the climax of the piece Duncan Rock’s Messenger hurled out the news that the divine Jocasta was dead Oramo really screwed up the orchestral tension in preparation for the return of that opening music. Suddenly the self-imposed constraints of Stravinsky’s well-practiced neo-classicism came crashing down.

You May Also Like

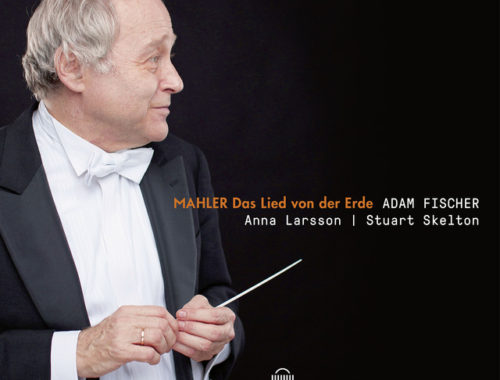

GRAMOPHONE Review: Mahler Das Lied von Der Erde – Larsson, Skelton, Düsseldorfer Symphoniker/Fischer

14/06/2019

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – July 2021

27/07/2021