Philharmonia Orchestra, Nelsons, Royal Festival Hall

The heroics came fast and fervently with Andris Nelsons and the Philharmonia Orchestra emerging from suffocating pianissimi to rip out the exultant fanfares of Beethoven’s Leonora No.3 Overture as if already limbering up to take on Strauss’ critics in Ein Heldenleben. That he saw them off so decisively didn’t, on his present form, come as much of a surprise. Nelsons doesn’t need anyone to fight his battles for him – not even the egotistical Strauss.

This was an evening of much trumpeting, offstage and on. Indeed when Hakan Hardenberger came on to play the familiar Haydn Concerto it was as if he’d momentarily descended from the battlements of the Beethoven. Suavely attired like the star he undoubtedly is, he tossed off the Haydn with crisply articulate aplomb. It was all so effortless, so natural – all those shifts of colour from rounded and bugle-like to down-and-brassy. The short, flashy cadenza in the first movement sounded like his own, zipping as it did up to piccolo trumpet regions, and all those grupetti in the finale could not have sounded further from the tongue-twisters we know them to be. And because he made it all sound so easy, this much-loved party piece felt like short measure for such a showman.

Hardenberger and Nelsons plainly thought so, too, because they sneaked in (unprogrammed) another, rather sexier, offering from HK Gruber, oddly entitled Three Mob Pieces. Clearly this was an offer no one could refuse and armed with three trumpets – an E-flat, a D, and a Piccolo – Hardenberger set about smooching and syncopating to his heart’s content against an instrumental backdrop which one felt was a whisker away from hanging loose on the cabaret scene. Hardenberger’s iridescent long coat was now entirely in keeping and he played like a dream. Gruber should stick to this stuff – it’s when he gets serious that he comes off the rails.

And so to fighting the good fight for Strauss. Nelsons had him stride forth with fabulous assurance, the Philharmonia string basses digging deep, the eight horns flaunting their sumptuous alliance with the cellos. This was as ripe a reading as they come with the leader Zsolt-Tihamér Visontay turning in a portrayal of Strauss’ “helpmate” – Pauline de Ahna – so feisty and assertive that one really did question who wore the trousers in this relationship.

More trumpetings from offstage and then the decisive battle – and, boy, was it decisive. Trombones spectacularly bore down on the ever plunging bass lines, trumpets were stopped high above the fray, and those horns covered themselves in glory. But more potent still were the two suspenseful silences, broken only by the grumbling of the fattest critics, the tubas, prompting a review of Strauss’ life’s work as egotistical as it is moving. The boisterously animated Nelsons grew still now and the closing pages, ending on the Also Sprach sunset – the final trumpetings or even “the last trump” – were noble indeed.

Where do I begin?

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – December 2020

06/01/2021

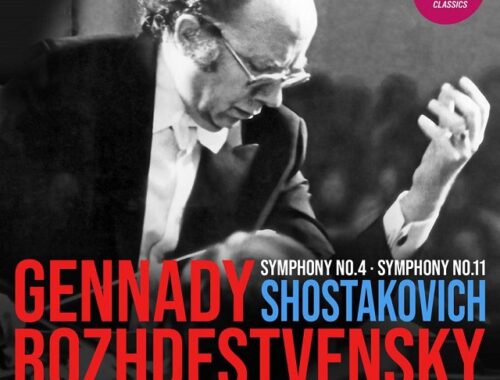

GRAMOPHONE Review: Shostakovich Symphonies Nos. 4 & 11 ’The Year 1905’ – BBC SO/BBC Philharmonic/Rozhdestvensky

06/01/2023