Philharmonia Orchestra, Capucon, Norrington, Royal Festival Hall

These days Sir Roger Norrington tends to stop, look, and listen rather than get stuck in; it’s almost as if it is someone else’s performance and not his own that he is enjoying. While the hive of activity that is Vaughan Williams’ Overture The Wasps buzzed busily around him it was a case of lazily marking out the bars (why beat it in four when one will do), occasionally cueing up a strategic string bass pizzicato and smiling benignly at that rather nice tune. Even the Philharmonia needs a little more hands-on intervention than this – it felt like a rehearsal play-through.

At least he could conscientiously take a back seat and enjoy his soloist – the super suave French cellist Gautier Capucon – in Elgar’s Cello Concerto. The opening flourish didn’t quite co-ordinate with the orchestra’s first chord (more vagueness from Norrington) but the arrival of shy violas and that theme was affectingly remote. What Capucon gives us is very Gallic for sure with big and intense tone and much contrasting finesse. But Elgar thrived on his swagger and the scherzo, with fizzing rhythmic articulation in the bow action, was everything the Vaughan Williams was not – dashing and edge-of-seat. Richly drawn bows then marked out the slow movement and if Norrington hadn’t inexplicably broken the tension and allowed the ailing audience a protracted mucal clearance the arrival of the finale would have felt more like a transition. Capucon regained his composure, though, and the great valedictory epilogue rolled out, ardent then fragile, the light fading fast.

He also gave us a bonus – and to the glistening arpeggios of Hugh Webb’s harp transformed himself into Saint-Saens’ The Swan and with seamless bowing glided over a melodic line as silken as his mane of black hair.

Norrington’s big turn (apart from sorting out his score and putting on his glasses – something of a drama in itself) was Holst’s The Planets, though that, it has to be said, was somewhat hit and miss as if being viewed through a dodgy telescope. What was especially unexpected, given his allegiance to pacey period style, were the generally deliberate tempi, not least “Mars” which weighed in heavily (great trombones) but without the scarifying remorselessness suggested by the allegro marking.

Mercury’s winged messenger seemed to have been afflicted by a Christmas work-to-rule and Neptune’s barlines failed to evaporate, the mysticism thoroughly compromised by a lack of real piano playing and celestial voices which didn’t fade from our hearing but simply stopped like an industrial walk-out. Back to the Planetarium, I fancy.

You May Also Like

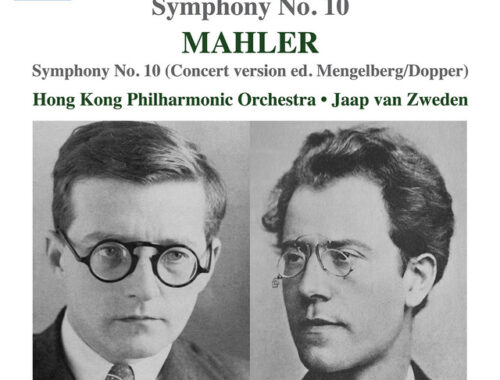

GRAMOPHONE Review: Shostakovich Symphony No 10, Mahler Symphony No 10 – Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra/van Zweden

27/02/2023

GRAMOPHONE Review: Copland: Quiet City / Dvořák: Symphony No. 9 ‘From The New World’ / Ives: ‘Holidays’ Symphony – Solistes Européens Luxembourg/König

17/10/2019