Orchestra of the Accademia Nationale Di Santa Cecilia, Pappano, Anvil Basingstoke

The Orchestra of the Academia Nazionale Di Santa Cecilia, Rome, brought a little something home grown on this their fleeting UK tour. While their counterparts at the Royal Opera in London were tracing out the ethereal opening measures of the Prelude to Verdi’s Aida, over at the Anvil in Basingstoke the self same music was about to spring a sizeable surprise.

It isn’t generally known or often heard but Verdi devised a more substantial Overture or Sinfonia for the Italian premiere of his popular opera only to think better of it during initial rehearsals at La Scala. The opening is a carbon copy of the original prelude but the storm clouds of ethnic strife soon sweep the music into an agitated state of flux with only Aida’s first act prayer repeatedly resurfacing to remind us of the human cost.

Actually the treatment is very Lisztian and served here as a hectoring curtain raiser to the orchestra’s tour guest Boris Berezovsky who whisked us into the extravagant world of Liszt’s First Piano Concerto with all the swagger and throw-away loucheness of a classical lounge pianist. The orchestra equally made their presence felt with a saturated, super-deep pitch into the opening flourish from the their highly distinctive string section – the bedrock of a flavourful sound. Not surprisingly there’s something “vocal” about all these players, individually and collectively, not least the solo clarinet and brilliantined first bassoon. Berezovsky led from the front in terms of fire-power and those chordal fusillades whipped up the requisite excitement. It was never tasteful but it was showy – right down to the ill-advised encore of the closing march which, of course, failed to deliver the accumulative excitement of the first time around.

But then the orchestra played Mahler – the First Symphony – and their singing quality was immediately apparent as the composer’s “Wayfarer” stepped out into the brave new dawn, cellos shaping his song with affecting naturalness. When Mahler himself conducted the orchestra on two separate visits to Rome he doubtless relished their characterisation of his music’s more parodistic elements – like the cheesy café music of the third movement here given a touch of the Italian street sound with their first trumpet (a real artist) lending a “home made” quality.

Those strings sang the second subject of the finale like a bel canto aria and I liked Pappano’s volatile way with the big tempo contrasts. It was bold, big-hearted, a little rash, thoroughly Mahlerian.

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – July 2020

22/07/2020

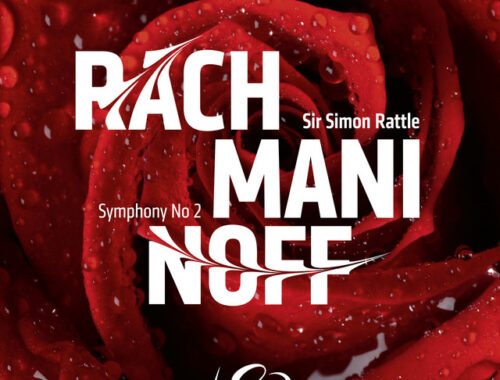

GRAMOPHONE Review: Rachmaninov Symphony No. 2 – London Symphony Orchestra/Rattle

19/05/2021