Mitsuko Uchida, Musicians from the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Wigmore Hall

Exactly what constitutes “the End of Time” in Olivier Messiaen’s extraordinary Quartet for piano, violin, cello and clarinet? Not surely “the end of days” but rather the end of measured time; music unfettered, music of the spheres, music without frontiers. Famously written when Messiaen was “doing time” in a camp for prisoners of war this unique expression of faith, of eternal life unbounded, was his “escape” in every sense of the word – and to hear it played with such astonishing abandon and consummate musicianship by Mitsuko Uchida and three Musicians from the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra – Daishin Kashimoto, Ludwig Quandt, and Wenzel Fuchs – was one of the highlights of this or any other musical year: a free pass to a parallel universe where music has long departed the page where it once it may have been written down.

Exactly what constitutes “the End of Time” in Olivier Messiaen’s extraordinary Quartet for piano, violin, cello and clarinet? Not surely “the end of days” but rather the end of measured time; music unfettered, music of the spheres, music without frontiers. Famously written when Messiaen was “doing time” in a camp for prisoners of war this unique expression of faith, of eternal life unbounded, was his “escape” in every sense of the word – and to hear it played with such astonishing abandon and consummate musicianship by Mitsuko Uchida and three Musicians from the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra – Daishin Kashimoto, Ludwig Quandt, and Wenzel Fuchs – was one of the highlights of this or any other musical year: a free pass to a parallel universe where music has long departed the page where it once it may have been written down.

But how to arrive at that lofty vantage point? I would have preferred just to have arrived at Wigmore Hall and heard only this one perfect work in glorious isolation. But audiences expect, and venues enjoy their bar sales, and 50 minutes, however astonishing, still apparently leaves some people feeling short-changed. Me, I had forgotten the Berg and Schubert which prefaced the Messiaen by close of play, or rather “end of day” – not because it wasn’t fine and revealing and made perfect sense musically but because the Adagio from Berg’s Chamber Concerto and Schubert’s Notturno in E-flat both represented a past that Messiaen had all but left behind and the “in the heat of the night” passion of the Berg, revealing for the first time the fiery intensity of Daishin Kashimoto’s violin playing, and the Schubert, played with a broad high-flown inevitability – now serene, now aflame with grandstanding flourishes – ultimately felt like merely points of departure for a destination unknown.

And so we arrived in that place, mindful of Messiaen and friends in Stallag VIIIA with scraps of paper for manuscript, a battered upright piano, and a cello with three strings, receiving this music “for the End of Time” from heaven knows where and sharing it with 5000 grateful souls good and ready to be transported. As were we, a tenth of that number, at Wigmore Hall. As I say, the thrill was in the abandon of this performance, the temperament, the risks taken, but all of it anchored in Messiaen/Uchida’s piano where myriad chords reverberated like gamelan gongs and torrential cascades opened the heavens. There were the “eternal” serenades for cello and piano – songs of sunset, both; the hearing-is-not-quite-believing clarinet playing of Wenzel Fuchs whose supernatural pianissimi swelled to unearthly crescendos and whose birdsong in the third movement suggested an ornithological penchant for jazz. The unison sixth movement “Danse de la fureur, pour les sept trompettes” was breathless cosmic dancing indeed with Wenzel’s clarinet a veritable Gabriel finally cleaving the sound barrier with his highest reachable note. And there was Quandt’s cello playing in the seventh movement where he in effect became an ondes martenot, scooping and swooping up and down the fingerboard.

But what finally silenced an irritatingly consumptive audience was Daishin Kashimoto’s “song without an end” in the final movement which in its intense alliance with Uchida’s piano was so charged that it took us beyond all recognisable emotion to some other plane of hearing and feeling. Uchida’s fading bell-like chords at the close were so quiet and so clean and so barely voiced that they should not have been possible on any piano that I know. Indeed, I’m not sure I really heard them at all.

You May Also Like

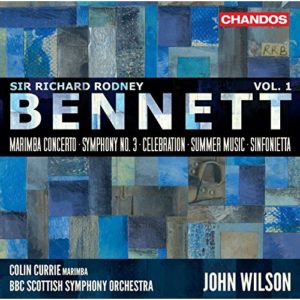

GRAMOPHONE Review: Richard Rodney Bennett Orchestral Works Vol. 1 – BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra/Wilson

30/01/2018

COMPARING NOTES with LUCY SCHAUFER

14/10/2021