London Philharmonic Orchestra, Jurowski, Royal Festival Hall *** (Review)

Opera with and without words, with and without voices – the London Philharmonic Orchestra’s new season began with a typically provocative piece of Vladimir Jurowski programming: an intriguing juxtaposition of the ripest Strauss and Zemlinsky affording dissatisfaction in just about equal measure but for very different reasons.

Strauss and Hofmannsthal’s fantastical operatic allegory Die Frau ohne Schatten takes the dubious and now politically very incorrect premise that no woman is whole unless fertile and all the high-flown symbolism and phantasmagorical melodrama in the world cannot disguise its skewed morality. In the absence of words and voices we are left with a shimmering celeste and glass harmonica festooned orchestral tapestry – an overload of Strauss at his most willfully exotic – but the stitch-up of “orchestral excerpts” which Jurowski presented here with such relish, whilst by no means unprecedented (I’ve heard it presented in this way before and shame on Boosey and Hawkes for once again sanctioning it), made no musical sense whatsoever. Those of us who have wallowed in the opera in spite of ourselves know and love its “best bits” – like the glorious longing of the Emperor’s aria or the solo cello’s re-echoing of his torment or the resounding percussion-laden crescendo of his petrification or the stonking final quartet – will have been content to relive them with the absent voices and context weighing heavily on our imagination, but for all the lushness and heft of the LPO’s playing, with its extra brass and offstage wind machine and thunder sheets, the joins and jump-cuts and musical non sequiturs made for an extremely expensive dog’s dinner.

There was, of course, method in Jurowski’s madness and the unveiling of Zemlinsky’s rarely heard one-act opera A Florentine Tragedy after Oscar Wilde immediately revealed the close proximity and shared DNA of the two composers. The tumultuous prelude – Straussian and then some – more than hinted at a domestic scenario (as in the Strauss) given an almost cosmic dimension. But the psycho-sexual hogwash of the ensuing hour – what price love, fidelity, adultery? – was played out in music so gushingly, wearisomely, indigestibly, sensual that the big twist at the end with the husband’s aggression acting like an aphrodisiac on his sullen wife felt totally unearned. Time and again I was put in mind of Strauss’ Salome (again Wilde) rather than Die Frau, the merchant husband’s baiting of his adulterer houseguest suggesting Herod’s of his stepdaughter. And when Guido Bardi (Sergei Skorokhodov) resists the merchant’s invitation to play the lute (there is, of course, one in the orchestra – almost obligatory for that period) the parallel with Salome’s refusal to dance is more than suggested in a lurid waltz emerging from Zemlinsky’s orchestra. The soloists, not least Albert Dohmen (as the husband Simone) whose role is tantamount to an enormous monologue, fought a losing battle with the orchestra in terms of balance, only Heike Wessels (as Bianca, the wife) emerging with clarity and dramatic conviction. Jurowski plainly adores this piece and as ever I applaud his adventurous spirit as music director of the LPO that he goes the extra distance to share it with us. I just wish I could be at all grateful.

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE Review: Nielsen Violin Concerto, Symphony No 4 – James Ehnes, Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra/Gardner

27/06/2023

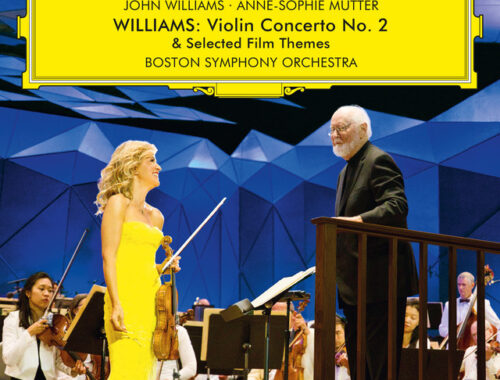

GRAMOPHONE Review: John Williams Violin Concerto No 2 & Various – Mutter, Boston Symphony Orchestra/Williams

20/07/2022