London Philharmonic Orchestra, Hannigan, Jurowski, Royal Festival Hall

Vladimir Jurowski deemed this the most challenging of any programme in the South Bank’s year long The Rest is Noise festival and proceeded to tell us precisely why. That his little preamble lasted almost twice as long as the first piece – Webern’s Variations for Orchestra Op.30 – was an indicator of just how scientific the thinking behind his programme was. Jurowski instinctively understands how and why works impact on each other in the way they do. Intellectually and emotionally speaking this was a classic of its kind – and with one possible exception the accomplishment of its execution was as exemplary as it was gripping.

Vladimir Jurowski deemed this the most challenging of any programme in the South Bank’s year long The Rest is Noise festival and proceeded to tell us precisely why. That his little preamble lasted almost twice as long as the first piece – Webern’s Variations for Orchestra Op.30 – was an indicator of just how scientific the thinking behind his programme was. Jurowski instinctively understands how and why works impact on each other in the way they do. Intellectually and emotionally speaking this was a classic of its kind – and with one possible exception the accomplishment of its execution was as exemplary as it was gripping.

In Webern’s penultimate work the reduction of his compositional sauce was as intense as it would get. The beauty of this highly enigmatic, even cryptic, piece is in its forensic clarity and the precision of what the London Philharmonic Orchestra achieved here under Jurowski’s analytical eyes and ears was startling. As abstract as this piece sounds on the surface, Jurowski achieved the near-impossible of infusing phrases of maybe one or two notes with feelings so transitory and yet so strong that collectively they added up to a whole emotional landscape. A solo violin here, a horn there, a thought, a question, an exclamation – a world of music in seven minutes.

From there we worked backwards through the dark times of the Second World War and the disturbing events preceding it. The Symphonic Pieces from Alban Berg’s unfinished operatic masterpiece Lulu are fashioned like a maxi-trailer for the finished article – snapshots of an unlikely heroine’s life and death. This was the big central piece of the evening and Berg’s voluptuous orchestra was wielded with astonishing richness of tone and colour. Through the opening Rondo (Andante and Hymn) Lulu’s world of men opens up to us, the cool seductive etchings of vibraphone and saxophone lending decadence to the harmonic yearning. And then Lulu herself entered, short skirt, fur collar, lethally high stilettos, loitering without intent against the wall of the platform as if living the Ostinato interlude (the accompaniment to a silent film showing her trial and imprisonment for the murder of her husband) in her mind’s eye.

Barbara Hannigan, the pre-eminent Lulu of our day, then slinked centre-stage to deliver her “Song”, her short but heartfelt confessional of who she is and how independently she stands from what men choose to make of her. It is directed at the one man she truly loves – Dr. Schön – and it is his theme which deep in the chest register of the violins pours out in the final scene of the opera, Jurowski here pointing up the inescapable proximity of Mahler.

The brilliance and ingenuity of the programme was then consolidated in two great works for antiphonal string orchestras and percussion, the one inspired by the other. And it was here that I questioned if Jurowski’s decision to use the largest conceivable body of strings for Bartok’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste did not compromised the tightness of the interplay in the up-tempo movements. It felt more Mondrian-like than it can – very linear, very abstract, and less subjugated to the mood music associations of a Stanley Kubrick thriller or indeed a Hermann/Hitchcock shower scene.

But how much more engaged and emotive was the performance of Martinu’s Double Concerto for two string orchestras, piano and timpani modeled as it is on the Bartok and rightly following it. The outer movements of this piece are all about driving resistance and the LPO strings gave us just that. The sonorous Chaconne at its heart is as impassioned a statement of that as could be imagined with Catherine Edwards‘ accomplished solo piano invoking a terrible feeling of isolation as Martinu’s Czech homeland is signed over to the Nazis. Small wonder the full-blown return of the Chaconne at the close is so defiant. Jurowski made that moment tell, and how.

What an extraordinary concert.

You May Also Like

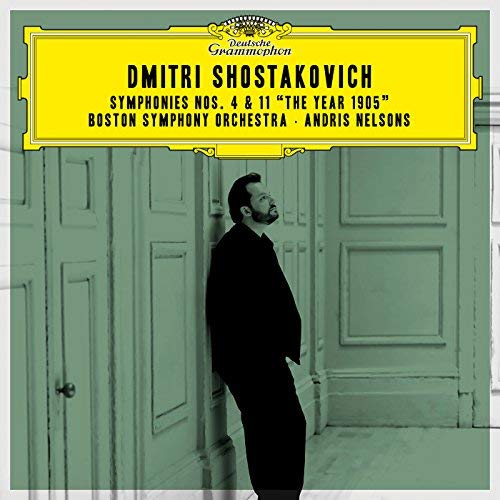

GRAMOPHONE Review: Shostakovich Symphonies 4 & 11 – Boston Symphony Orchestra/Nelsons

15/09/2018

A Conversation With JULIAN LLOYD WEBBER

02/06/2011