London Philharmonic Orchestra, Fleming, Eschenbach, Royal Festival Hall

With Wagner’s Tannhäuser Overture raising the curtain, so to speak, Renée Fleming arrived like Venus in a soufflé of black and bronze layered chiffon. Or to be more in keeping with the Strauss Four Last Songs she was about to sing, a gown fit for a Countess. No one makes an entrance or wears a frock quite like Fleming: she is in every sense a star turn – and if you’ve got it (and she has, in spades), flaunt it, I say.

She certainly flaunted the Strauss. But whereas there once was a time when words were very much secondary to the effusion of sound, now they are attended with almost obsessive care, pointed, articulated, artfully coloured a la Schwarzkopf (the distinctive “chesting” on words like “nacht”) as to sound almost “conversational” in the operatic sense. It seemed to me that you couldn’t hear or feel the line for the detail within it.

Of course, that fabulous sound will out and in the first song “Frühling” the arching melisma on the word “wunder” (“miracle”) was momentarily glorious. Likewise the “unguarded spirit” taking wing in “Beim Schlafengehen” where one at last felt that Fleming was allowing the music to carry her rather than the other way about. “September” brought halting rubato in its middle stanza while the valedictory “Im Abendrot” was long-breathed and then some. I love this singer for her bel canto values, for the relish with which she deploys her fabulous instrument – but this account of Four Last Songs was simply too calculated, too complicated, too fussy, to be moving.

Christoph Eschenbach shadowed and accommodated Fleming’s every nuance adoringly and the London Philharmonic Orchestra played most beautifully – and should there have been any fears that the Strauss might colour the ensuing Beethoven 7, they were quickly dispelled. There was certainly amplitude in this big-boned, double-wind, affair but it was strangely joyless, indeed stern in the extreme.

Eschenbach seemed hell-bent on underlining the work’s inexorability with a pointed attacca from one movement to the next. But the overriding impression was one of accents and sforzandi unbounded; a heaviness prevailed, and it was not until the penultimate climax of the finale that the lid finally came off the performance and in the crossfire of first and second violins a regeneration of heat and propulsion finally saw elation triumph over effort.

You May Also Like

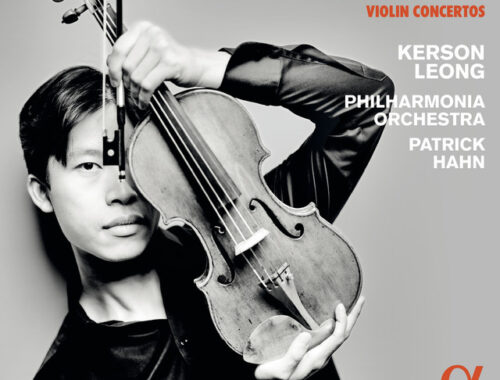

GRAMOPHONE Review: Britten & Bruch Violin Concertos – Kerson Leong, Philharmonia Orchestra/Hahn

07/08/2023

GRAMOPHONE Review: War Paint – Original Broadway Cast Recording/Frankel

23/05/2018