London Philharmonic Orchestra & Choruses, Jurowski, Royal Festival Hall **** (Review)

Working backwards from Rachmaninov’s Choral Symphony “The Bells” Vladimir Jurowski’s latest confection in the new London Philharmonic season was an extraordinary resourceful and cleverly juxtaposed sequence of tintinnabulations, real and imagined, actual and suggested, celebratory and mournful – the ringing that in all cases evaporates into silence.

Working backwards from Rachmaninov’s Choral Symphony “The Bells” Vladimir Jurowski’s latest confection in the new London Philharmonic season was an extraordinary resourceful and cleverly juxtaposed sequence of tintinnabulations, real and imagined, actual and suggested, celebratory and mournful – the ringing that in all cases evaporates into silence.

Miaskovsky’s Silentium (a UK premiere) was central, descending like a shroud over the concert, some of music’s darkest colours swept up by winds of change. This brooding and impassioned piece has a dark and turbulent heart, a kind of Scriabinesque Francesca da Rimini where the buffeting of the devil wings arrives in a flurry of trilling clarinets, bell’s raised for optimum penetration and chill factor. The inspiration behind this “symphonic parable” was Edgar Allan Poe’s prose tale “Silence: A Fable”. Poe would, of course, later invoke a whole panoply of bells for Rachmaninov.

But first there was Schedrin’s Concerto for Orchestra No.2 “The Chimes” (UK premiere) picking up on Rachmaninov’s recognition of the bell ringing that has chronicled the advance of Russian history for centuries. Bells or the imitation of bells prevail throughout Schedrin’s virtuosic concerto. Fanfares in brass and woodwinds chime with the tinkling of assorted metallophones, cushioned hammers give way to metal beaters on exposed piano strings, and furious piccolo alarums are cut short by a single gunshot. An orchestral revolution quelled. Silence.

Denisov’s Bells in the Fog (UK premiere), as suggested by the title, was more impressionistic, its musical atmospherics – the isolated chiming of often single notes – only fleetingly offset by anything – simmering string chromatics here, a brassy flourish there – which might be construed as emotional.

Rachmaninov’s sleigh bells might have emerged from the lifting of such a fog, his deft orchestral shimmerings pointedly avoiding the sound of actual sleigh bells, the tenor soloist – Sergei Skorokhodov – imploring us to “listen” until the choir demands that we do. It was at this point that I realised why Jurowski had insisted upon the combined choruses of the London Philharmonic and London Symphony – the impact was of a mighty communal roar with the movement’s brilliant trumpet-topped climax achieving maximum thrill-factor. The sheer heft of the sound in the rowdy scherzo suggested the agitated throngs of Boris Godunov, metaphorical alarm bells vying with trenchant snatches of the Dies Irae in the strings.

Words have their own music, of course, and Jurowski’s all-Russian soloists gave his choirs a sound, a tinta, to emulate. Tatiana Monogarova’s voluptuous “bride” found desire in every phrase of the second movement while Vladimir Chernov was the weathered harbinger of death grimly reaping towards “the stillness of the grave”. As that moment approaches how poignantly Rachmaninov invokes a short but ravishing lament (a mere handful of notes) in the mournful chest register of the violins. Moments like that attest to his greatness and here was a performance that left none of us in any doubt. These were the last notes he wrote before leaving Russia and if a single phrase could convey the depth of his heartache that short but highly charged lament was surely it.

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – February 2021

24/02/2021

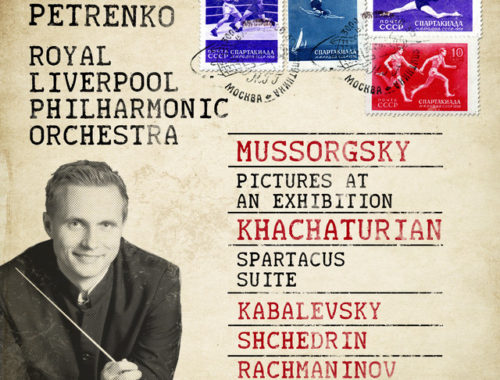

GRAMOPHONE Review: Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition / Khachaturian Spartacus Suite, Etc. – Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra/Petrenko

26/02/2020