Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Kavakos, Dindo, Chailly, Barbican (Review)

For the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra’s second residency at the Barbican Centre Riccardo Chailly pulled focus on an entirely new sounding Brahms. Gone were all those bad performance practices, bad habits, from the early 20th century, gone was the lingering romanticism, the willful soupiness, and in with a vengeance came a classical rigour, a lean and hungry vitality. Like so much of what we have come to expect of Chailly the first of this four concert series with its attendant side events brought a total re-evaluation of the composer: no longer the conservative romantic, the polar opposite of Wagner (as was the received wisdom in his day), but a complex and innovative symphonist who broke as many of the rules as he obeyed. Enter a rebellious Brahms.

Chailly is neatly lining up the four symphonies with the four concertos – and first up were Leonidas Kavakos and Enrico Dindo in the Double Concerto. The opening statement from the orchestra was a throwing down of the gauntlet if ever I heard one: emphatic, arresting, cut to the bone. Cellist Enrico Dindo then soliloquised in Shakesperian fashion, a whole range of colours suggesting a whole range of emotions, all within a couple of minutes. Kavakos’ violin parried but the drama, gruff and gritty as it was, was in the conversation, now conciliatory, now confrontational. The telepathy, chemistry, call it what you will, between Kavakos and Dindo was self-evident and challenging and even that prayerful slow movement tune refused to linger. Mellow it was not.

And so to the first of the symphonies – 14 years in the making – sounding like it was determined to make up for lost time. That lowering opening coming up through the bass lines, timpani carving a path through the mire, violins reaching for light, was as arresting as it’s ever been, an imperative alla breve. That was to be Chailly’s defining way throughout the piece with the allegro of this opening movement determined to shake off disillusionment. It smouldered.

The deep and abiding consolation of the slow movement with the deep echo of string basses beautifully realised brought gorgeous singing oboe playing and radiant work from the Leipzig concert master. How different this movement sounded with a century of soupy sentiment stripped away.

The finale had a surprise or two up its sleeve, the desolate pizzicato of the opening paragraph falling like rain from the gathering clouds. I’ve never heard it in quite the same way before. And how good to hear the burnished horn solo and ensuing chorale freed of portentousness. Chailly managed the switch from the big “ode to joy” theme into Brahms’ impulsive allegro con brio with a exhilarating upping of the tempo and when he and Brahms finally broke free in the coda the momentary disbelief at the reckless abandon of the tempo thrillingly demonstrated jut how conditioned we had become. Bring on the rest.

You May Also Like

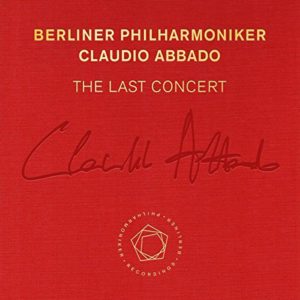

GRAMOPHONE Review: The Last Concert – Claudio Abbado/Berlin Philharmonic

17/07/2018

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – February 2022

21/02/2022