Julia Fischer, Martin Helmchen, Queen Elizabeth Hall

With the truly great composers – and I count Schumann among them – there is that abiding sense of music being created in the playing of it. It is, in effect, like a stream of consciousness in which we, the listeners, are spookily complicit. With Schumann, though, the experience is that much more intense as every theme, every unpredictable twist and turn, seems to evolve from the moment by moment impulse of personal revelation. The sense of imperative in this music is extraordinary and hearing his three violin sonatas in one sitting is like living with him through three years (1851-1853) of his troubled life.

That sense of living in the moment was something that Julia Fischer and her wonderfully articulate partner Martin Helmchen made great capital of in their poetic and gripping performances. The symbiosis between them – and that’s something which cannot be manufactured – paid significant dividends throughout. Tension and release was always at the core of the drama and the masterful Fischer, who can come across as a bit of a cool customer (the entirely “proper” and modest hausfrau image certainly contributes to that), conveyed here a touching vulnerability attending Schumann’s beautiful themes with a true sense of their emotional fragility. Her bow was more often than not discreetly light on the string – a ghostly, grazing, contact at times – and such passages as that darkening and lightening harmonic progression at the close of the first sonata’s first movement typified the music’s propensity for disturbing mood swings.

Both the 2nd and 3rd Sonatas begin and end with declamatory gestures caught somewhere between anxiety and affirmation. This troubled soul certainly weathers some storms and in those passages Fischer and Helmchen were tumultuous. Yet more extraordinary, though, were the inward-looking moments of stasis like that dying resonance from the violin at the close of the first movement of the A minor third sonata or the distracted ruminations of the D minor second – strange, disembodied music which sometimes sounded like it was being heard from an entirely different room.

Then again, could there be anything more present or reassuring than the serene and mildly Brahmsian second movement of the third sonata, so simple and so perfect. A serenade for Schumann’s beloved Clara? Fischer and Helmchen made it personal enough to be just that.

You May Also Like

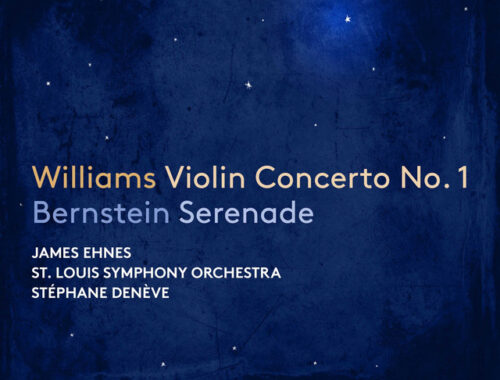

GRAMOPHONE Review: BERNSTEIN Serenade / WILLIAMS Violin Concerto – James Ehnes, St Louis Symphony Orchestra/Denève

03/06/2024

Edward Seckerson meets CELINDE SCHOENMAKER

23/03/2023