Humperdinck, Hansel and Gretel, Royal Opera House

The moment of truth in any staging of Hansel and Gretel must be the Dream Pantomime which closes act one. This is the director’s moment, the moment where the entire premise of the production finds fulfillment in some of the most beautiful and harmonically luminous music to emerge from the turn of the 19th century. Moshe Leiser and Patrice Caurier (in a revival of their 2008 staging) go for whimsy and kitsch underlined by one inescapable reality. As forest animals don feathery wings to become the children’s guardian angels, what do we imagine might complete the vision of homely Christmas Day bliss unfolding before our eyes? What might be the two greatest gifts that the children could imagine unwrapping? Well, put it this way: when we are hungry we dream of food.

This isn’t the first time that a director has introduced the shadow of deprivation into this scene. Richard Jones did so unforgettably in his staging for Welsh National Opera and later the New York Met. But where Jones infused his entire production with a Brothers Grimm grimness, Leiser and Caurier dilute the message with a clean-scrubbed ordinariness in act one where the restrictive confines of the children’s bedroom – floated, as it were, in the regressive perspective of the forest – doesn’t suggest deprivation or poverty at all.

Things improve greatly with the arrival of Jane Henschel’s carnivorous Witch – a comely pensioner replete with mumsy cardigan, support stockings, and zimmer frame. Only her huge and scary voice gives her away – that and a freezer full of dead children, their carcasses hanging like so much meat in an abattoir. Popping freshly floured children into her industrial ovens is soon revealed as the secret of her outsized gingerbread men.

Henschel’s big voice (and for one here’s a witch who really sings the role) is but one of a particularly well-endowed company. Christine Rice is a strapping, vocally butch and incisive, Hansel and Ailish Tynan’s lyric soprano has grown immeasurably of late to prove the perfect match for Rice, bright, confident, and luminous right up to ringing top C. The evergreen Thomas Allen gives us a wonderfully well-rounded portrayal of Father, rich of voice and vivid of text and again well matched to Yvonne Howard’s heroic mother.

What Rory MacDonald’s conducting lacks in reach and opulence it gains in rhythmic and harmonic clarity – and that’s something that this performance’s dedicatee – the late, great, Sir Charles Mackerras – would have applauded. All that remains is for the lost children to gorge themselves on the Gingerbread Witch, fresh from the oven.

You May Also Like

A Conversation With LINUS ROTH: Crusading for Weinberg

17/09/2014

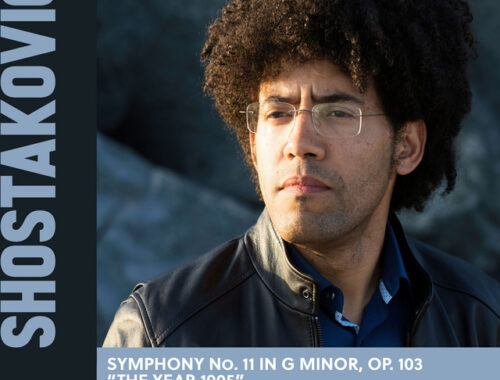

GRAMOPHONE Review: Shostakovich Symphony No. 11 – San Diego Symphony Orchestra/Payare

10/08/2022