GRAMOPHONE Review: Sibelius Complete Symphonies – Oslo Philharmonic/Makelä

There’s something extraordinarily satisfying about embarking upon Sibelius’ entire symphonic journey in a single one-day sitting. The evolution and refining of language and expression, the juxtaposition of the romantic and the radical is clarified and renewed. Total immersion. And that’s pretty much what happened with this cycle in the Spring of 2021 when the Oslo Philharmonic under their new Chief Conductor – Klaus Mäkelä – played nothing else. To say that Mäkelä has generated something of a buzz in the industry is an understatement for sure (he is only the third conductor to be signed exclusively to Decca in 90 years) but perhaps I can best sum up first impressions of his qualities by saying that what radiates from him is a thorough sense of the organic allied to an in-the-moment imperative.

There’s something extraordinarily satisfying about embarking upon Sibelius’ entire symphonic journey in a single one-day sitting. The evolution and refining of language and expression, the juxtaposition of the romantic and the radical is clarified and renewed. Total immersion. And that’s pretty much what happened with this cycle in the Spring of 2021 when the Oslo Philharmonic under their new Chief Conductor – Klaus Mäkelä – played nothing else. To say that Mäkelä has generated something of a buzz in the industry is an understatement for sure (he is only the third conductor to be signed exclusively to Decca in 90 years) but perhaps I can best sum up first impressions of his qualities by saying that what radiates from him is a thorough sense of the organic allied to an in-the-moment imperative.

So much of the musical energy of these symphonies stems from rhythm and articulation, from a propulsive sense of inevitability – and that’s something that Mäkelä has mastered to a fault. He also has a theatrical nose for atmosphere which is apparent from the moment that desolate solo clarinet at the start of the First Symphony surveys the landscape that will become Sibelius’ enduring musical canvas. We tend to think of this piece in terms of its drama and big tunes and less of its unanswered questions. But through the latter Sibelius is finding his voice and though Mäkelä doesn’t make it quite the thrill-ride of the Gothenburg/Rouvali account on Alpha Classics hearing it in the context of what it to follow accentuates the long view it takes. Which is not to say that Mäkelä doesn’t relish the sweep of the drama – he most certainly does – but just as surely as the big tune in the finale comes up through the bass lines to soar and conquer so too are we mindful of the radiant horizon evaporating in a couple of desultory pizzicati. Elusive and inconclusive.

And so we move on to the Second – which is quite marvellous – the epigrammatic nature of the first movement’s halting themes at once secondary to the irresistible urge to move forward. Frosty-keen woodwinds vie with throbbing strings to establish a folksy elemental quality all of its own. Mäkelä is very ‘vocal’ with the Oslo strings at the climax but it’s the direction of travel that is so gripping. And as we arrive in the craggy and forbidding landscape of the second movement it’s the indomitable spirit that Mäkelä makes us feel through the soles of our feet (those bass lines again). I love his poetic, wistful way with the trio of the scherzo (beautiful oboe playing) but then comes the transition into the finale and that blaze of nationalism (and optimism) in the broadest sense. That tune is fervent without being portentous and in the coda the string tremolandi burn phosphorous bright.

I like the first movement of the Third to be a shade slower but understand that it’s a study in momentum. Then again there’s that sudden diversion into no-man’s-land after the opening paragraph which Mäkelä makes clear is a moment of questioning where we are going. The second movement may come across like a ‘simple song’ but Mäkelä is mindful of its elusiveness especially the way it drifts into nocturnal musings in the strings.

The concision of the Third is, of course, a feature in itself and that ability to cut things back to the bare bones in the quest for a new and purer kind of expression truly comes home in the Sixth. The late Colin Davis described the opening as amongst the most beautiful kinds of polyphony we have. Like an illuminated manuscript. It’s all about crystal clarity, this piece, and Mäkelä and his Oslo players sound refreshed in the playing of it.

How far removed that is from the unfathomable plunge at the start of the Fourth Symphony. ‘Searching’ is the word I always reach for to describe the extraordinarily personal nature of the piece: that cello solo at the outset is something very inward indeed. A shroud. The Fourth is forever striving to penetrate the darkness and stave off an all-consuming solitude – it’s about seeking but not finding. As presented by Mäkelä the closing pages of the finale are disturbingly inconclusive, almost cryptic. His reading has depth and reach and whilst the dark heart and soul of the piece – the slow movement – may not allude to Mahler in the way that Karajan extravagantly does (a good or a bad thing?) its strenuous attempts to achieve resolution is vividly conveyed and when the really big climax finally arrives the rising trombone line is truly seismic.

But the sun does rise again in the heroic Fifth and Mäkelä absolutely capitalises on the release of its musical energy. Leonard Bernstein first alerted me to the Dionysian dance which emerges from the first movement’s celebrated sunrise and carries us through to the exultant coda – and so does Mäkelä. The gradual accelerando should and does here feel organic, a gathering of energy towards the brilliant trumpet-led peroration. In the middle movement – where subtext is all – the big central modulation is ear-opening in its harmonic intrigue and come that uplifting finale and famous coda Mäkelä and his Olso brass rejoice magnificently in the most consonant dissonance in all music. Those final chords sound, as they should, like a cosmic punctuation of silence.

To a great extent this music finds its own space – and that’s the overriding impression that Mäkelä conveys. The evolution of the Seventh is grippingly chronicled, the great trombone orations arriving like stations of the cross. This is the most intimate of epics, kindred spirit to Tapiola which chills and electrifies here with elemental force. The pianopianissimo prior to the howling snowstorm which consumes the piece is indescribably other-worldly in its effect. As is hearing the Three Fragments of manuscript (one lasting only 14 seconds) which may or may not have been sketches for an Eighth Symphony and are Sibelius’ cryptic last words here.

We all have favourite recordings and cherished performances of the Sibelius symphonies but Mäkelä’s cycle is all of a piece, accomplished, insightful, and full of the beauty and intrigue that make these symphonies so perennially exciting. An uber-auspicious debut.

You May Also Like

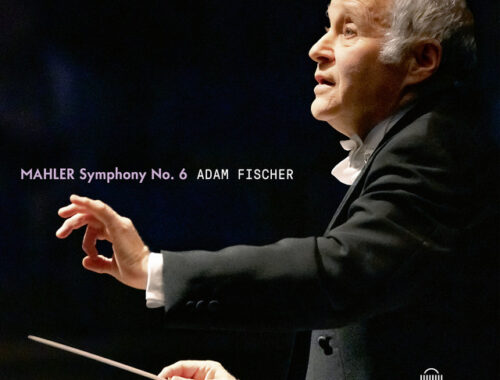

GRAMOPHONE Review: Mahler Symphony No. 6 – Düsseldorfer Symphoniker/Fischer

21/02/2022

BBC Radio 3 Record Review Podcast: Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms

17/07/2021