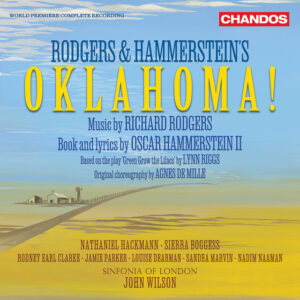

GRAMOPHONE Review: Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! – Soloists, Sinfonia of London/John Wilson

This is important. Oklahoma! was a big moment – perhaps the big moment – in musical theatre’s ‘coming of age’. Granted that sixteen years earlier Oscar Hammerstein II and Jerome Kern had already called time on the term ‘musical comedy’ with the mightily ambitious Show Boat – but Oklahoma! was the moment when all the elements of song, dance, and spoken word seemed to coalesce into a dramatic character-driven whole. I guess the word is integral. So it’s good to hear the score ‘complete’ (and what’s more from a proven stylist) – not for completeness sake but because even without great swathes of Hammerstein’s book we have a very real sense of how the piece rolls, how songs become ‘scenes’ and how the dance elements in those scenes are woven into the fabric of the whole with dance breaks serving a dramatic purpose rather than simply a diversion.

This is important. Oklahoma! was a big moment – perhaps the big moment – in musical theatre’s ‘coming of age’. Granted that sixteen years earlier Oscar Hammerstein II and Jerome Kern had already called time on the term ‘musical comedy’ with the mightily ambitious Show Boat – but Oklahoma! was the moment when all the elements of song, dance, and spoken word seemed to coalesce into a dramatic character-driven whole. I guess the word is integral. So it’s good to hear the score ‘complete’ (and what’s more from a proven stylist) – not for completeness sake but because even without great swathes of Hammerstein’s book we have a very real sense of how the piece rolls, how songs become ‘scenes’ and how the dance elements in those scenes are woven into the fabric of the whole with dance breaks serving a dramatic purpose rather than simply a diversion.

Honestly, listening to John Wilson’s super-stylish recreation is like setting the time machine to 31 March 1943 and taking your seat in the St James Theatre just as the overture is about to strike up. Not that even the best of Broadway pit bands could compete with Wilson’s hand-picked Sinfonia of London, authentic to the precise number of players and the distinctive sound of Robert Russell Bennet’s original orchestrations (painstakingly restored by R & H’s Bruce Pomahac). The precision is hair-raising as those blistering violins go all hoe-down on us at the start of the orchestra. Rhythm, rhythm, pulsing rhythm. We’ve forgotten how this score actually sounds over the decades of revival and reinvention and if we were in a theatre not listening to an album we’ll have forgotten how ‘acoustic’ sounds. None of the contemporary over-hyped, over here, electronic enhancement or even ‘sampled’ replacement but honest to goodness robustness and heart. Just sixteen string players – even so, unthinkable now – but listen to Wilson’s violins in the first appearance of ‘Out of My Dreams’, small in number but big and fat in phrasing and sound and portamento and then again the perfect tempo and ‘vintage’ colouring of ‘Many A New Day’ and the fizzing point and counterpoint of the title song. It’s that word again ‘style’ and with it comes a freshness and newness that is all about respecting what is there and not what isn’t.

So every song, every reprise, every entrance and exit and underscored dialogue is here and in a number like the ‘conditional’ love duet ‘People Will Say We’re in Love’ we can enjoy the full measure of the scene coming in and out of music and spoken word and applause points in preparation for an even more radical realisation of the device in Carousel two years later. Wilson’s Laurey and Curly – Sierra Boggess and Nathaniel Hackmann – lead his tight-knit company of proven stylists, Hackmann easy and mellifluous, Boggess pure and bell-like but full of character and feistiness in that head-chest mix. I almost didn’t recognise Louise Dearman in Ado Annie though the money notes still pop and Jamie Parker (Will Parker) was born to the delivery of this era. We’ve also another side of eligible leading man Nadim Naaman as Ali Hakim in the normally cut ‘It’s a Scandal! It’s an Outrage!’

Then there’s Rodney Earl Clarke’s Jud, the character which has undergone the biggest evolution if you’ve seen the recent ‘reimagining’ in London’s West End or on Broadway. Making him less of an outsider and seriously ‘eligible’ as a rival to Curly was probably a step too far for Hammerstein in 1943 and his strange number ‘Lonely Room’ emphasises that ‘otherness’. He’s also pointedly mocked in ‘Poor Jud is Dead’ (a savagely funny Hammerstein lyric) which makes Laurey ‘making up her mind’ almost a formality.

That, of course, is the great centrepiece of the show – the Dream Ballet – born out of the most delectable of Rodgers waltz songs ‘Out of My Dreams’. And this is where Wilson’s scholarship and authenticity really comes into its own. The storytelling is now physical – no words, purely dance, with Rodgers’ key songs now providing the emotional memory for almost fifteen minutes of stage time. It isn’t on the level of the equivalent (and climactic) sequence in Carousel but Wilson and his band really meld the disparate elements and create a satisfying, and again innovative, whole.

The title song, when it finally arrives, is as exhilarating and punchy and uplifting as the prospect of a brand new state and if you’d been in the theatre back in March 1943 you’d have been on your feet, too.

You May Also Like

A Conversation With VASILY PETRENKO: On Shostakovich

02/09/2010

A Conversation With SUSAN BULLOCK

02/09/2010