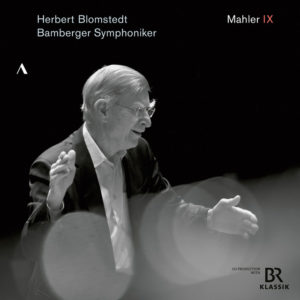

GRAMOPHONE Review: Mahler Symphony No. 9 – Bamberg Symphony Orchestra/Blomstedt

School of Barbirolli. That was my first thought as the faltering pulse of the opening bars ushered in the warm and consoling first theme, first heard, of course, in the second not first violins. No hint so far that a dark night of the soul might be imminent. There is fire in the belly of the beast as the first great climax washes over us and Blomstedt is sure to emphasise the cynical sneer of Mahler’s stopped horns. But the impending nightmare is as yet at arms length.

School of Barbirolli. That was my first thought as the faltering pulse of the opening bars ushered in the warm and consoling first theme, first heard, of course, in the second not first violins. No hint so far that a dark night of the soul might be imminent. There is fire in the belly of the beast as the first great climax washes over us and Blomstedt is sure to emphasise the cynical sneer of Mahler’s stopped horns. But the impending nightmare is as yet at arms length.

So this is a reading of Mahler’s last completed symphony (though, of course, it is actually his Tenth since Das Lied von der Erde was deliberately, superstitiously, given no ordinal number) which for all its defiance and resilience takes a mellower view of its long day’s journey into night. It is less febrile, less neurotic than those readings from Bernstein or Tennstedt or even Abbado. The incremental building of the first movement is intense rather than unhinged though each successive ‘collapse’ certainly deliver with the roar of trombones at the biggest of them (the climax of the development) quite tremendous. But Blomstedt is more about the shadowy recesses of this first movement and the tenderness he ultimately coaxes from the resourceful Bamberg Symphony Orchestra.

The inner movements suggest that the hero of the piece (that is, Mahler himself) may go rather more quietly into the dark night. The second movement ländler favours good natured ebullience over any suggestion that it might indeed be a dance of death. It’s a gentler, less punchy, country dancing. Charm rather than menace exudes. Even the contra bassoon at the close sounds cuddly. And then comes the Rondo – Burleske which has rigour but no real teeth. Again, even the uncouth ‘off key’ E-flat clarinet has no malice and barely a hint of derision when he mocks the trio’s attempt to dig deeper. Those pages – with their poetic premonition of the finale – are indeed heartfelt, the dying glissando in flute and oboe not ugly but entirely serene.

The Bamberg strings are a warm embrace in the finale and the generous saturation of sound towards the far-reaching horizon reminds us just how extraordinary this movement is. But ultimately Blomstedt offers a more intimate, less ‘cosmic’, letting-go and in his refusal to hint at the infinite by taking all the remaining time in the world over those last pages as Abbado and certainly Bernstein do (Abbado prefers to invoke his eternal silence after the music stops) means that one comes away from this performance with less of a sense of finality. It wasn’t Mahler’s last word, of course, but it was still a hard-fought-for peace and Mahler without the neuroses just isn’t the full story.