GRAMOPHONE Review: Mahler Symphony No. 4 – Düsseldorf Symphony Orchestra/Adam Fischer

Adam Fischer launched his Düsseldorf Mahler cycle with an accomplished and individual account of the nighthawkish Seventh Symphony. I commented at the time that his brother Ivan should be looking over his shoulder. More so now. This Fourth is even better. Its Wunderhorn playfulness offsets a knowing old-world charm where phrases turn on a sixpence and all manner of characterful nuance lifts it out of the commonplace.

Adam Fischer launched his Düsseldorf Mahler cycle with an accomplished and individual account of the nighthawkish Seventh Symphony. I commented at the time that his brother Ivan should be looking over his shoulder. More so now. This Fourth is even better. Its Wunderhorn playfulness offsets a knowing old-world charm where phrases turn on a sixpence and all manner of characterful nuance lifts it out of the commonplace.

I love that all the Mahlerian exaggerations and heightened contrasts are in almost wilful defiance of the finesse of the reading. The work’s childishness and petulance is an integral part of it and pulling these excitable flights of fancy out of the bag can only be achieved by super-responsive playing. The intricacy of detail here (balance, phrasing, dynamics) makes even the familiar sound new and unexpected. And taking Mahler at his word, edging him out of even his comfort zones, is the key to rekindling its newness. There is a clear trust and mutual respect between Fischer and his Dusseldorf Symphony and not one bar – in marked contrast to the recent Gergiev/Munich account – is taken for granted.

As I write I am recalling the pungency of the first movement climax whose exuberance really is infantile and whose raucousness is dominated by the noisiest child of all – the E-flat clarinet – pinging through at the top of its voice. Likewise the sour fiddler of the second movement’s spooky dance of death egged on by the spiky klezmer band clarinet and an awkward bassoon lumbering into the trio section.

The eiderdown of strings at the start of the slow movement surprises by virtue of the fact that Fischer keeps the sound inward and intimate. In fact he conspicuously avoids an over-gilding of the movement’s yearning and actively resists over-emoting. No overt tearing at the heart-strings here. Heaven will come in good time. Even the great E-major epiphany is so Disneyesque – cascading strings and harps very prominent – that we instinctively know this to be a child’s glimpse of heaven. Mahler, the adult, is more preoccupied with the variants he fashions from his two main themes. Fischer plays with them knowingly.

I like Hanna-Elizabeth Muller’s sweet tone and lively storytelling in the finale, the child within us enjoying the prospects of a joyful afterlife while the now agitated sleigh bells from the first movement seem to be telling us otherwise. As the music sinks into a contented slumber one (not least Mahler) is already wondering what it will awaken to.

I eagerly anticipate the rest of this Mahler cycle. I’ve no doubt that fresh insights will this way come – but better yet I won’t know what to expect of them.

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE Review: Dear Evan Hansen – Original Broadway Cast Recording/Pasek & Paul

08/11/2017

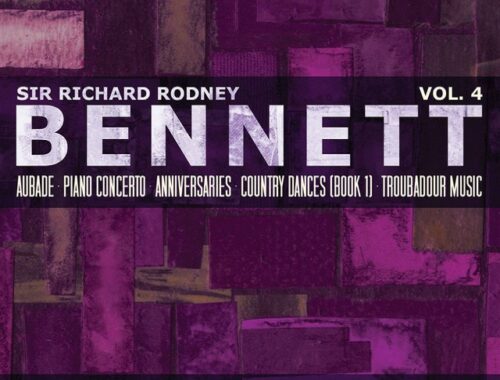

GRAMOPHONE: Richard Rodney Bennett Orchestral Works Vol. 4 – Michael McHale, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra/Wilson

22/07/2020