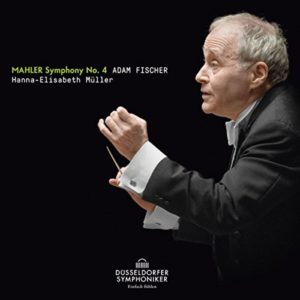

GRAMOPHONE Review: Mahler Symphony No. 2 ‘Resurrection’ – Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Daniele Gatti

As Mahler symphonies have become better and better known over the years so too has the pressure grown on his interpreters to rekindle their “newness”, their ability to surprise and shock. I have nothing but the highest regard for Daniele Gatti and his magnificent Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, steeped as they are in a long and distinguished Mahler tradition, but what is most impressive about this account of the Second Symphony is also that which sometimes makes it wanting in intrigue and excitement. The risks which Mahler took so often and so readily – exaggerating as he did all the trappings of Austro-German symphonic music – are here so well-honed as to render them, if not benign, then certainly less startling and threatening than they might be.

As Mahler symphonies have become better and better known over the years so too has the pressure grown on his interpreters to rekindle their “newness”, their ability to surprise and shock. I have nothing but the highest regard for Daniele Gatti and his magnificent Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, steeped as they are in a long and distinguished Mahler tradition, but what is most impressive about this account of the Second Symphony is also that which sometimes makes it wanting in intrigue and excitement. The risks which Mahler took so often and so readily – exaggerating as he did all the trappings of Austro-German symphonic music – are here so well-honed as to render them, if not benign, then certainly less startling and threatening than they might be.

You know immediately from the outset of the first movement that Gatti is meticulous in his observation: the full value of that suspenseful tremolando between upheavals in cellos and basses is scrupulously observed. But how nerve-wracking does it feel? And should there be more abandon in those seismic cellos and basses? When the second subject is revealed in full the second time around doesn’t Mahler want it to arrive much more cautiously from the mists of time? He does ask for precisely that feeling – and when he asks he has the best possible reasons for doing so. You cannot “normalise” or short-change Mahler’s flights of fancy in any way.

Gatti makes much of the creepy slow marching basses at the start of the approach to the big development climax but despite the promise of big contrasts to come, as suggested by his writ-large ritardandi, the gradual headlong dash to the abyss (not headlong enough) doesn’t begin to convey the recklessness of the music with the ensuing – and shocking – molto pesante not nearly pronounced enough at the arrival of those shattering discords.

But then again the long reflective, rather “sentimental”, passage for strings just prior to the coda is vintage Concertgebouw – very beautiful. As is the homely Andante minuet of the second movement, where the turbulent middle section for once comes as a real surprise. An interrupted idyll. Again, though, there needs to be more of a sardonic edge to the third movement and a touch of “cheesiness” to the close harmony trumpets of the trio which Gatti, with no relaxing of the tempo, makes far too “tasteful” to my mind.

Karen Cargill’s engagement is characteristically total in the “Urlicht” where she and Gatti quite swiftly but eloquently maintain the line resisting the temptation to “do a Bernstein” on the song. I love, too, the distancing of the trumpets (how many don’t observe this) at the start and the heartbreaking oboe playing.

Watching Gatti on the DVD highlights his attention to detail, not least in the manner of phrasings and dynamics, and he is totally in command of the superstructure in the “Judgement Day” finale. But here again I would question one crucial choice. The great “march of the undead” is almost Klemperer-like in its deliberation and like Klemperer in that famous (but in my view very flawed) recording it puts grandeur ahead of scarifying impetus. But, that said, the maniacal offstage band really does get appreciably closer and the Concertgebouw trombones are pretty terrifying in that tumultuous last-ditch climax.

Gatti’s expansiveness is key to his reading of this last movement and from the flute’s songful bird of paradise and the heart-stopping entry of the chorus right through to his sensationally slow peroration (a leaf from Bernstein’s book here) I have no problem with it. It sounds marvellous and is, as ever, glorious in its cumulative effect. You could argue that the last 20 minutes of this symphony are pretty much conductor-proof. But then I turn to Vladimir Jurowski’s London Philharmonic Live performance and the euphoric uplift of the final pages comes as a revelation once more. That’s the version that repeatedly surprises and astonishes me the most.

You May Also Like

A Conversation With PAUL KERRYSON: ‘The Light in the Piazza’

02/09/2010

A Conversation With DARIO MARIANELLI

02/09/2011