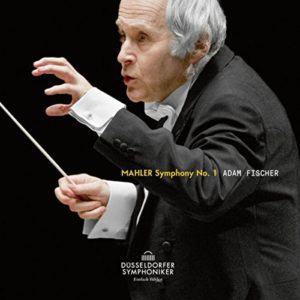

GRAMOPHONE Review: Mahler Symphony No. 1 – Düsseldorfer Symphoniker / Fischer

This is a terrific account of Mahler’s fledgling symphony – full of the rashness and impetuosity of youth and the wild imaginings that go hand in hand with it. Each time that eight-octave-deep “silence” of the opening page sounds, hazy violin harmonics tracing a haze of light on the dawn horizon, you have to wonder at this 20-something’s daring holding to the rules of symphonic form while seeking new dimensions with his nose for theatre.

This is a terrific account of Mahler’s fledgling symphony – full of the rashness and impetuosity of youth and the wild imaginings that go hand in hand with it. Each time that eight-octave-deep “silence” of the opening page sounds, hazy violin harmonics tracing a haze of light on the dawn horizon, you have to wonder at this 20-something’s daring holding to the rules of symphonic form while seeking new dimensions with his nose for theatre.

Adam Fischer has a nose for theatre, too, and one can imagine how long he and his engineers spent, for instance, getting the distancing of the off-stage trumpets just right in the opening pages. He judges the ambling “wayfarer” theme just right, too, as light and airy as can be and with that first-time freshness. Then there is mystery as shadows fall across the music in the development – a sense of wonder at adventures to come. But most of all in this first movement there is excitability. The explosion of fanfares at the climax is a release of energy and then some but it is the exuberance of the wayfarer theme set free and romping home that has more than a touch of Bernstein about it.

The middle movements are if anything even more ripely characterised than in Bernstein’s glorious Royal Concertgebouw recording. The lumpen scherzo is earthy and coarse with rosiny strings digging into its stomping rhythms and Mahler’s stopped horns especially vivid sniggering in the reprise. The trio is shy and awkward in its attempts to be graceful and then it’s more of the knees-up with Fischer whipping up the tempo and making capital of the whooping horns.

I’d like to have heard a slightly less beautiful tone from the solo double bass (at least it’s solo) at the start of the eerie third movement – but the delivery of that favourite children’s song sounding so forlorn (the first of a lifelong succession of funeral marches) still gives one chills and Fischer’s exaggerated tempo-rubato throughout this movement is full of the spirit of the backstreet coffee house with its Klezmer band of well-meaning locals. It’s heavy with Mahlerian irony, that distinctive juxtaposition of pathos and bathos, with the rosy trio – hushed and beautiful here – full of homely well-being.

If I have a single reservation about Fischer’s reading – and he is far from being alone in this – it concerns his tempo for the stormy allegro of the finale which for all its shock and awe is for me just a hair’s breadth – and I mean a hair’s breadth – short of pace towards that last degree of reckless imperative. Tiny adjustments make all the difference in Mahler. But there is so much here to enjoy: the heart-easing violin glissando into the second subject, phrased with unaffected honesty; the magical return to the symphony’s opening material where the returning second subject is suddenly more meaningful in the context of all that has gone before; and the barnstorming “titan” of a coda where Mahler’s rather trite triumphal theme (with horns standing, of course – more “visual” theatre) assumes such gung-ho confidence.

There is an extraordinary kinship and telepathy between Fischer and his Dusseldorf orchestra. They may not be the most glamorous sounding ensemble in the world but the heart and spirit of the playing sweeps all before it. This is shaping up to be the most idiomatic and exciting cycle of Mahler symphonies since Kubelik and Bernstein.

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE Review: Richard Rodney Bennett Orchestral Works Vol. 1 – BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra/Wilson

30/01/2018

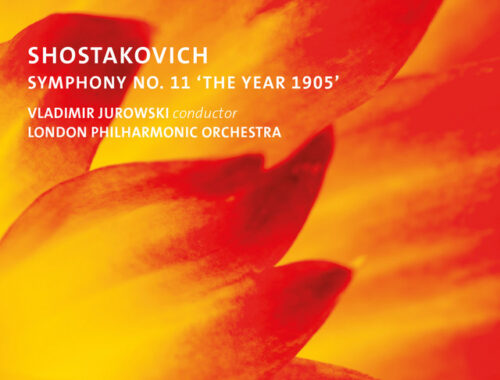

GRAMOPHONE Review: Shostakovich Symphony No. 11 ‘The Year 1905’ – London Philharmonic Orchestra/Jurowski

09/12/2020