GRAMOPHONE Review: Heggie ‘Woman: the making of…’ – Lillian Farahani/Maurice Lammerts van Bueren

“Woman the making of…’ Intriguing title. And it takes its cue from Jake Heggie’s very first commission – written in 1995 to original texts by Philip Littell – which was, to borrow a more iconic title, ‘all about Eve’. Eve-Song is, like his subsequent pieces in the song-cycle format, as much a monodrama or dramatic scena as the companion work on this album – At the Statue of Venus – yet another collaboration (2005) with the extraordinary Terrence McNally whose plays and musical theatre librettos are so bountiful in their theatricality. Eve and Rose – the two featured characters – ‘might not seem to have a lot in common’, says the liner note, ‘but they are sisters to the core.’ Heggie, the die-hard feminist, is in his element.

“Woman the making of…’ Intriguing title. And it takes its cue from Jake Heggie’s very first commission – written in 1995 to original texts by Philip Littell – which was, to borrow a more iconic title, ‘all about Eve’. Eve-Song is, like his subsequent pieces in the song-cycle format, as much a monodrama or dramatic scena as the companion work on this album – At the Statue of Venus – yet another collaboration (2005) with the extraordinary Terrence McNally whose plays and musical theatre librettos are so bountiful in their theatricality. Eve and Rose – the two featured characters – ‘might not seem to have a lot in common’, says the liner note, ‘but they are sisters to the core.’ Heggie, the die-hard feminist, is in his element.

All that I have thus far written about Heggie (and it is a lot) boils down to one simple statement of fact: that he has theatrical bones. He instinctively knows how music chimes with words, how it can underline, enhance, intensify, or simply complement what is sung rather than spoken. Eve-Song plays with the stigma of ‘original sin’, of woman born of man… (‘Damn it!’). From the wordless chant of the opening – a kind of primal wail of protest – Eve, the everywoman of the title, works through her resentments, her lusts and temptations (the snake and the apple are shrouded in a louche bluesyness), her retaliations (‘Woe to Man born of woman’), her maternal desires. It is typical of Heggie that he should turn the primal wail of the opening in to a gentle lullaby at the close. A tiny touch of genius. That said, I think he’s grown tenfold since this piece and if I’m honest I can’t see myself returning to it often when there is so much else to savour. But I can see why a singer like Lilian Farahani would want to make a fist of it, especially as the companion piece, the McNally scena, makes for such a natural bedfellow (if you’ll forgive the implication).

Heggie has written two operas with McNally (Dead Man Walking and Great Scott) and made a masterful setting of the final scene from Master Class, McNally’s gripping piece about one of his obsessions, Maria Callas. At the Statue of Venus finds Rose, a successful businesswoman, waiting on a blind date in a museum. We’ve all been there (even if we haven’t) and McNally amusingly nails the anxiety and apprehension and awkwardness and false alarms inherent in the situation. Best of all, though, is a wonderful departure at the heart of the scene where Rose recalls the dream of love, of loving, of being loved as a flashback to childhood. And it’s as if McNally already knew what Heggie would make of his words and could already hear the memorable melodic ‘hook’ which brings them so tenderly off the page. It is, if you like, his Barber Knoxville moment. And, of course, there’s a neat pay-off still to come.

Again Farahani clearly loves and seeks to honour the material as self evidently as her pianist Maurice Lammerts Van Bueren whose task is positively orchestral at times. But Farahani is no DiDonato in terms of acting through song. The material is super-challenging, I know, but it’s all a little lacking in variety, both in terms of colour and dramatic inflection.

Good to have the pieces in the Heggie discography, though, and the handsome presentation offers a visual storyboard of dramatic photographs to accompany and amplify the texts.

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE Review: Jurowski Conducts Stravinsky Vol 1 – Angharad Lyddon, London Philharmonic Orchestra/Jurowski

02/10/2022

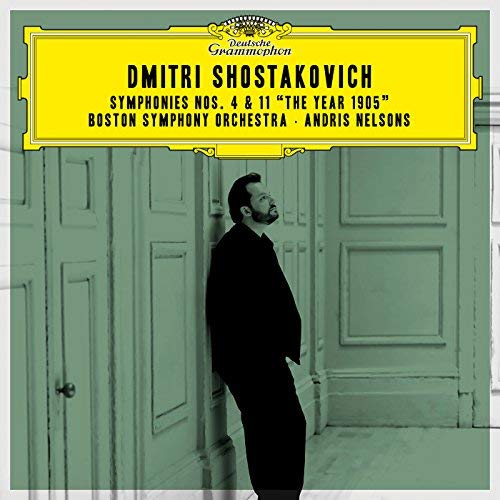

GRAMOPHONE Review: Shostakovich Symphonies 4 & 11 – Boston Symphony Orchestra/Nelsons

15/09/2018