GRAMOPHONE Review: Burnished Gold – Robyn Allegra Parton/Simon Lepper

It is refreshing to encounter a singer – Robyn Allegra Parton – whose gifts of curation are it would seem fully equal to her musicianship. You might argue that the album’s artwork is a sprinkling of gold-leaf too far – Klimt mock-ups invariably look like cheap parodies – but as a convenient metaphor for the sea-change in creativity marked by the look and feel of the Succession artist’s visuals, they at least give notice of the aural titillation to follow. New horizons come into focus through the dreamy and decorative impressionism of these composers – three of which rarely grace live or recorded showcases of this repertoire.

It is refreshing to encounter a singer – Robyn Allegra Parton – whose gifts of curation are it would seem fully equal to her musicianship. You might argue that the album’s artwork is a sprinkling of gold-leaf too far – Klimt mock-ups invariably look like cheap parodies – but as a convenient metaphor for the sea-change in creativity marked by the look and feel of the Succession artist’s visuals, they at least give notice of the aural titillation to follow. New horizons come into focus through the dreamy and decorative impressionism of these composers – three of which rarely grace live or recorded showcases of this repertoire.

Joseph Marx is one. His ‘Nocturne’ opens proceedings on to a heady world of shimmering ornamentation and wide-raging vocals that glide and weave and illuminate. The piano is very much an equal partner in this particular song and Simon Lepper’s ‘vocalise’ immediately suggests a unity of thinking and feeling between him and Parton. For her part the silvery quality of her voice coupled with the reach and seductiveness of its coloratura facility potentially lends itself to music centuries apart. There is, too, a curiosity, an inquisitiveness, in her response to these songs – why the notes are where they are in the first place and how they serve and communicate the poetry.

In the Strauss set she keeps the familiar ‘Morgen’ simple. Rapt and limpid and inward, avoiding the all too familiar (and somewhat ‘old world’) portamenti.

Lepper places the modulation to perfection. ‘Das Rosenband’ is about two souls forever entwined in love and the engaging flutter in Parton’s voice in and around the coloratura of the last stanza pulls us towards a transcendent melisma around the key word ‘Elysium’ (Paradise).

Erich Korngold was surely too young (a mere 14 when he wrote the first of the Sechs Einfache Lieder) to be peddling divine decadence – but the boy had to grow up fast in order to keep up with his prodigious gifts and the proof is in something like ‘Liebesbriefchen’ which is essentially a ‘thinking of you’ song where Parton’s scaling back of the sound achieves optimum intimacy. We are, after all, talking about reaching for the stars here. Less is infinite.

Then there is Berg and the increasingly core Sieben Frühe Lieder taking us to a new level of rapture and drama and a sense that tonality is being longingly subverted towards a new freedom. The Nightingale’s song could be its last making it all the more rapturous, ‘Nacht’ is all enveloping in its mysterious shifting keys, and eternity beckons in ‘Traumgekrönt’.

Two women – Johanna Müller-Hermann and Alma Mahler – conclude the gold-leafed collection, the latter’s Vier Lieder highlighting the outrageous injustice of being effectively ‘silenced’ by her husband. The starkness of ‘Licht in Der Nacht’ belies its tonality and the tone of ‘Ansturm’ – essentially a dramatic recitative – is striking. Parton projects their anomalies knowingly and in the concluding hymn to nature Alma’s switch to an ecstatic vocalise – as in ‘no words adequate’ – perhaps demonstrates why Mahler wanted her silenced.

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – June 2018

20/06/2018

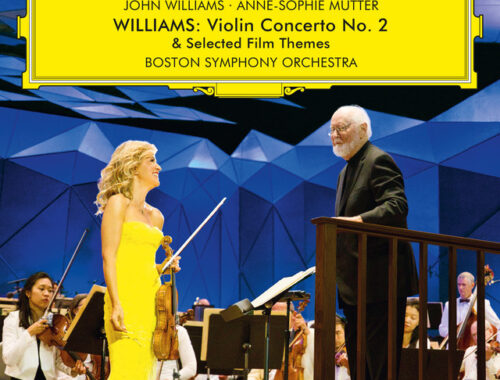

GRAMOPHONE Review: John Williams Violin Concerto No 2 & Various – Mutter, Boston Symphony Orchestra/Williams

20/07/2022