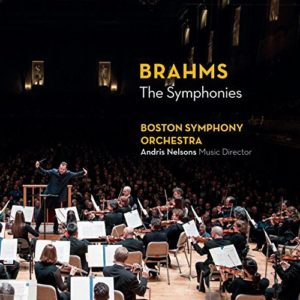

GRAMOPHONE Review: Brahms Symphonies 1-4 Boston Symphony Orchestra/Andris Nelsons

In a personal liner note for this set Andris Nelsons celebrates the recorded legacy of Brahms in Boston referencing complete cycles from Leinsdorf and Haitink and recordings of individual symphonies under Koussevitzky, Munch and Ozawa. Only a conductor supremely confidant in his own identity would venture to do so, of course, and Nelsons is nothing if not his own man in this repertoire, confounding expectations in some respects whilst confirming them in others. His Brahms is as vital and impulsive and rhythmic as all his work strives to be – though not as sheerly dynamic as one might have imagined – but there is blend and bloom, too, with Symphony Hall, Boston, seeming to accommodate this music from the bass lines upwards – a deep and sonorous sound.

In a personal liner note for this set Andris Nelsons celebrates the recorded legacy of Brahms in Boston referencing complete cycles from Leinsdorf and Haitink and recordings of individual symphonies under Koussevitzky, Munch and Ozawa. Only a conductor supremely confidant in his own identity would venture to do so, of course, and Nelsons is nothing if not his own man in this repertoire, confounding expectations in some respects whilst confirming them in others. His Brahms is as vital and impulsive and rhythmic as all his work strives to be – though not as sheerly dynamic as one might have imagined – but there is blend and bloom, too, with Symphony Hall, Boston, seeming to accommodate this music from the bass lines upwards – a deep and sonorous sound.

Nelsons talks of finding precisely the right character for each movement and in that he truly listens to the music, feeling its pulse and allowing the phrasing to evolve with as little intervention or “shaping” as possible. He is generous without indulgence, muscular without vulgarity. Just occasionally one senses him harnessing his natural dynamism in deference to the music’s noble pedigree. Perhaps I was expecting a higher degree of tension and excitement from the opening movement of the First Symphony? The promise is there in the tragically underpinned sostenuto of the opening – giving way as it does to the enticing woodwinds of the second lyric idea – but maybe the main allegro could be a shade more imperative.

That’s the thing about this music: you don’t want to unduly drive it but nor do you want to simply luxuriate in it. The second movement of the First brings to the fore the distinguished Boston woodwinds and a sense of the music evolving in the playing of it. And then there is the finale with storm clouds famously clearing with the BSO’s refulgent solo horn and a chorale of trombones to die for. Now the main allegro here is liberating for sure and perhaps Nelsons had been intentionally holding something in reserve because the climax leading to the return of the ubiquitous horn theme is rollocking indeed.

Anyone who thinks that Brahms was the conservative and Wagner the radical needs to think again. The evolution of the Second demonstrates how mindful Nelsons is of that. The myriad twists and turns and underlying threat of the autumnal first movement (where the deviation from and contortion of form is so pronounced) is boldly chronicled and the second movement – with wonderful string playing – is likewise gripping in the way Nelsons appreciates how daringly the material is developed. But the sun comes out again in the bracing finale and Nelsons is definitely off the leash. The return of the second subject is the warmest of hugs and the coda is exuberantly rip-roaring, descending trombones cutting through the texture like noisy bell chimes.

The Third Symphony is gorgeous. The first movement has what the Viennese might call schwung (Nelsons includes the exposition repeat) and the development really earns its climax. In the slow movement the aforementioned naturalness and fluidity of Nelsons’ phrasing (what musicality this man has) is possessed of a spontaneity that repays his belief in the music. The Bostonians really sing. And the celebrated poco allegretto of the third movement has the appropriate ache of nostalgia. Note, too, the magical evaporation of the finale’s coda: Nelsons’ Wagner tellingly referenced.

And so to the great Fourth. Again, don’t expect Toscanini. Nelsons builds the first movement’s head of steam by stealth measuring its expansive lyricism – and grandeur – with a growing resolve. The measured processional of the second movement evolves into something quite ravishing with the return of that second theme in the chest register of the Boston strings especially memorable. A similar voluptuousness arrives with the first variant of the chaconne finale and you can almost feel Nelsons channelling Brahms in the way he moves from one inspired improvisation to the next.

So, much to enjoy from an orchestra who seem to have found the perfect soulmate for this stage in their ongoing journey. The mutual respect and like-mindedness is palpable in each of these performances and whatever you may feel about this choice or that there’s always a very real sense of music-making happening “in the moment” and for that one time only.