GRAMOPHONE Review: BERNSTEIN Serenade / WILLIAMS Violin Concerto – James Ehnes, St Louis Symphony Orchestra/Denève

I’ve always admired the modesty and truthfulness of James Ehnes as a player – and you can hear that modesty at work in Phaedrus’ opening address from the Bernstein Serenade. There’s an unfussy directness about it that looks you straight in the eye and immediately draws you in. Only Bernstein, of course, could have fashioned a violin concerto from Greek mythology – namely Plato’s Symposium – and then drawn such innate theatricality from a group of great thinkers holding court in praise of love. But then again he loved words almost as much as he loved notes.

I’ve always admired the modesty and truthfulness of James Ehnes as a player – and you can hear that modesty at work in Phaedrus’ opening address from the Bernstein Serenade. There’s an unfussy directness about it that looks you straight in the eye and immediately draws you in. Only Bernstein, of course, could have fashioned a violin concerto from Greek mythology – namely Plato’s Symposium – and then drawn such innate theatricality from a group of great thinkers holding court in praise of love. But then again he loved words almost as much as he loved notes.

Pitching strings against percussion was also inspired, not because it was an original concept – it was, of course, a well-practised combo – but because that rhythmic élan adds a sense of ‘modernity’ to the mix and in the finale a ‘hipness’ that borders on the downright jazzy. This is such an inspiring well-made piece which both Ehnes and Stéphane Denève with his classy St Louis players savour to the full. ‘Agathon’ (effectively the slow movement here) is undoubtedly one of Bernstein’s most beautiful creations – the serenity of a lullaby with the intensity of love unbridled. And around it are flashes of brilliant characterisation that typically show the composer ‘on stage’. Small wonder it has been seized upon for ballet. It dances. I love that the scherzo ‘Eryximachus’, short and pithy, shows us a quick-thinker and that the aforementioned final celebration even gives us a cool bass pizzicato. If only Bernstein had lived long enough to see the piece take its rightful place in the core repertoire.

The John Williams Concerto No 1 (1974) feels like a natural coupling though in language it inhabits a rather different universe teetering as it does on the edge of atonality. We are indeed some distance from the galaxy far, far, away which is the Williams with whom we are most familiar. The expressiveness and lushness, though, is most certainly him and Bernstein would (and probably did) admire the musical gamesmanship.

The solo part has that improvisatory quality of being created – or ‘spun’ – in the playing of it and Ehnes really captures that illusion of in-the-moment invention. The slow movement is searching in every respect with the Williams of the silver screen only a whisker away and the opening of the finale has the drama of one well used to underscoring cinematic intrigue. But the overriding feeling here is one of rapture and the quiet middle section – with Ehnes deeply receptive – could, if only subliminally, be a close relation of Bernstein’s ‘Agathon’.

You May Also Like

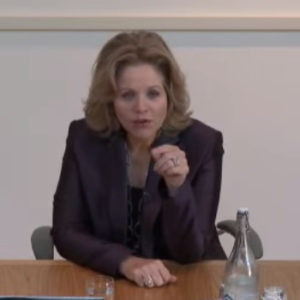

A Conversation With RENÉE FLEMING

02/12/2014

John Weidman on Pacific Overtures & collaborating with Stephen Sondheim

01/12/2023