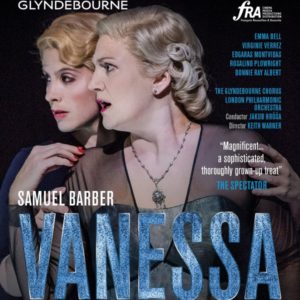

GRAMOPHONE Review: Barber Vanessa (BluRay/DVD) – Glyndebourne Festival Opera, London Philharmonic Orchestra/Hrůša

Since it was unveiled at last year’s Glyndebourne Festival Keith Warner’s handsome and insightful staging of Barber’s Vanessa has probably done more to silence the work’s naysayers than any in recent memory. It’s a piece that has in equal measure divided and baffled the musical cognoscenti over the years. What is it really about? Should we care about these self-pitying, self-indulgent women? Isn’t it all just a lot of hot air? That rather depends on how you approach it. Psychological thrillers are none too common in opera and the issue with Vanessa has always been how you put that on stage.

Since it was unveiled at last year’s Glyndebourne Festival Keith Warner’s handsome and insightful staging of Barber’s Vanessa has probably done more to silence the work’s naysayers than any in recent memory. It’s a piece that has in equal measure divided and baffled the musical cognoscenti over the years. What is it really about? Should we care about these self-pitying, self-indulgent women? Isn’t it all just a lot of hot air? That rather depends on how you approach it. Psychological thrillers are none too common in opera and the issue with Vanessa has always been how you put that on stage.

Keith Warner does a Hitchcock on it. And he does it with mirrors. Vanessa has covered all the mirrors in her isolated mansion. She awaits the return of her lover Anatol. Frightened of what she might see ‘through a glass darkly’ she looks only into herself. So Warner dwarfs her with gigantic moving mirrors, their reflections inescapable. Past, present and future merge – sometimes simultaneously. Noirish filmed projections heighten the surreal, dream-like quality and take us obliquely into the world of Rebecca, Vertigo, and Marnie. Lighting designer Mark Jonathan even lights it like a film noir. More revelatory still is the sense that Warner has created of Vanessa, her niece Erika, and the Old Baroness being three generations of the same woman. That a difference to one’s perceptions of the piece that makes.

I always think that one can judge the quality of an opera production by the extent to which it withstands close scrutiny. The close-ups here (and these ladies are all ready for them) are hugely revealing. Rosalind Plowright’s Baroness is a gaunt, watchful presence; Emma Bell’s highly-strung Vanessa is all pent-up frustration (sexual and otherwise); and in between Virginie Verrez’ Erika – a quite marvellous performance – is slowly but surely turning into both of them.

A vicious circle of love, deceit and betrayal is fuel in abundance for Samuel Barber’s heady brew – and it absolutely chimes with the Hollywood-infused lushness of his lyricism and somewhat overheated heft of his explosive orchestral tuttis. There are moments here which could just as easily have sprung from the pen of Hitchcock’s composer of choice, Bernard Herrmann. Indeed the underscoring of this melodrama is rendered all the more gripping by the way in which the voices are such an integral part of it. Set-pieces defer to the impulse and imperative of the sung dialogue. The work’s two most famous arias come early – Erika’s ‘Must the winter come so soon’ and Vanessa’s ‘He has come’ and they are essentially scene-setters for the impending drama. Book-ending them, the poignant quartet ‘To leave, to break’ is a summation.

But it’s all of a piece, no question, and thanks to Warner’s perception and motivation this excellent cast really deliver. As do Glyndebourne’s resident London Philharmonic under the dynamic young Czech Jakub Hrusa. Shadowy, opulent, effulgent – Barber’s Vanessa is the opera that bridges Hollywood and the Broadway stage.

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – June 2019

14/06/2019

GRAMOPHONE Review: Jurowski Conducts Stravinsky Vol 1 – Angharad Lyddon, London Philharmonic Orchestra/Jurowski

02/10/2022