GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – October 2020

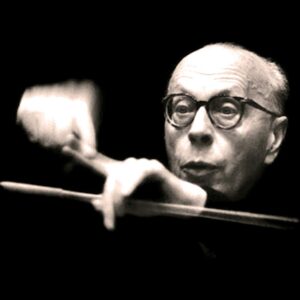

In a recent and far-reaching exchange with the conductor John Wilson (for an audio podcast to be found on You Tube) the names George Szell and Sir John Barbirolli (celebrated in the July edition) dominated our conversation at one point. A shared enthusiasm to be sure. We lost them both in the very same week back in 1970 and whilst Wilson didn’t have my memories of seeing them both in action live (too young) there were key recordings that had inspired him over the years. One was Barbirolli’s famous disc of English string music with the Sinfonia of London (now glorious reincarnated by Wilson) and Szell’s jaw-dropping account (with his Cleveland Orchestra) of Walton’s Second Symphony. It’s a work Wilson has been looking at (indeed all of Walton) in his ongoing exploration of repertoire despite knowing – as with Previn’s LSO account of the First Symphony – that it was unlikely to be bettered in terms of sheer brilliance and precision. It elevates the piece in ways that one couldn’t begin to imagine.

In a recent and far-reaching exchange with the conductor John Wilson (for an audio podcast to be found on You Tube) the names George Szell and Sir John Barbirolli (celebrated in the July edition) dominated our conversation at one point. A shared enthusiasm to be sure. We lost them both in the very same week back in 1970 and whilst Wilson didn’t have my memories of seeing them both in action live (too young) there were key recordings that had inspired him over the years. One was Barbirolli’s famous disc of English string music with the Sinfonia of London (now glorious reincarnated by Wilson) and Szell’s jaw-dropping account (with his Cleveland Orchestra) of Walton’s Second Symphony. It’s a work Wilson has been looking at (indeed all of Walton) in his ongoing exploration of repertoire despite knowing – as with Previn’s LSO account of the First Symphony – that it was unlikely to be bettered in terms of sheer brilliance and precision. It elevates the piece in ways that one couldn’t begin to imagine.

Szell was in my experience unforgettable live in ways that many of his recordings simply cannot convey. This Walton 2 was an exception, as were the Schumann Symphonies, his Vienna Philharmonic disc on Decca of Beethoven’s Incidental Music to Egmont, and a Mahler Knaben Wunderhorn with Schwarzkopf and Fischer-Dieskau. There was also a Tchaikovsky Fourth with the LSO which for some reason had to wait years for release. Perhaps Szell wasn’t happy with it (he was famously both a perfectionist and a firebrand) and refused to sign off on it in his lifetime?

But live – my goodness, that was another story. I remember an unforgettable Mahler Sixth under him (with the London Philharmonic) and the most thrilling Beethoven Ninth with the Philharmonia – never equalled in my experience. Janet Baker was the alto soloist and she recalls how very tricky he was until you learned how to handle him. Visits with his own Cleveland Orchestra were also memorable (a Barber Piano Concerto with John Browning) though I could never understand why Szell, a Hungarian, insisted on making a disfiguring cut in the last movement of Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra (the whole of that extraordinary passage where the music gathers energy towards the big restatement of the coda)? But he and Barbirolli were special in such different ways. You could feel it even before a single note was sounded. Sometimes the mystical quality of a performance – like Barbirolli’s Thomas Tallis Fantasia – is already signalled in the silence before the first downbeat.

Returning to Walton, I have one little story I shall treasure. Working my Saturday job as a teenager in the record department of a well known store I looked up one day to find the man himself standing before me and asking in that well-rounded voice of his if I had ‘Previn’s recording of Walton’s Second Symphony’. On composing myself I handed him a copy and nervously said ‘I think you’ll be well pleased Sir William’. He smiled at the recognition though little did he know that what I actually wanted to say was ‘It isn’t a patch on the Szell and certainly not a patch on Previn’s account of the First but still well worth hearing.’ The critic in me remained muted.

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – March 2020

25/03/2020

COMPARING NOTES: Laura Pitt-Pulford in conversation

05/01/2021