GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – October 2017

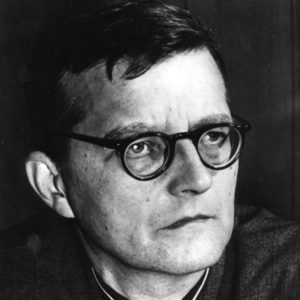

The dust may finally have settled on the 2017 Proms season but one strand of programming continues to resonate with me. In commemorating the 1917 Russian Revolution Vasily Petrenko and Vladimir Jurowski stepped up with stonking performances of both Shostakovich’s revolutionary symphonies. Jurowski reaffirmed the 11th ‘The Year 1905’ as the most underrated of the canon and Petrenko read the subtext – or ‘script’, as he likes to call it – of the hectoring 12th ‘The Year 1917’ with such ferocious clarity as to make us think that we had been getting this much-maligned piece wrong for years.

The dust may finally have settled on the 2017 Proms season but one strand of programming continues to resonate with me. In commemorating the 1917 Russian Revolution Vasily Petrenko and Vladimir Jurowski stepped up with stonking performances of both Shostakovich’s revolutionary symphonies. Jurowski reaffirmed the 11th ‘The Year 1905’ as the most underrated of the canon and Petrenko read the subtext – or ‘script’, as he likes to call it – of the hectoring 12th ‘The Year 1917’ with such ferocious clarity as to make us think that we had been getting this much-maligned piece wrong for years.

But it was a small but mighty concert from the 24-strong Latvian Radio Choir which effectively triggered the process of reassessment in my mind. This powerful rendition of selections from Shostakovich’s Ten Poems on Texts by Revolutionary Poets for chorus – a remarkable work – raised a number of interesting questions, not least why the wholesale quotation of revolutionary songs across both the aforementioned symphonies resonated so much more in the 11th Symphony (celebrating as it does the failed revolution of 1905 when the composer was one year old) than it did in the 12th, his long-awaited and long-averted ‘Lenin’ Symphony?

The shortest answer to that question is that Shostakovich was an extremely bad liar. The longer answer is that whereas the brutal suppression of the 1905 revolution still unlocked something profoundly personal within him some half a century after the event (you can hear it in the long and heartbreaking cor anglais oration in the finale of the 11th), celebrating Lenin’s idealism while the legacy of Stalin’s tyranny still festered was something he could not fully engage with. His heart just wasn’t in it.

The subtexts or ‘hidden codings’ in Shostakovich’s symphonies are much discussed. These often thinly disguised protests were designed to confuse, even hoodwink, the authorities, to deflect criticism and even curry favour from them in Stalin’s Soviet Union. How you read them – and this is especially pertinent to his interpreters – can totally change the way we hear a piece. The coda of the 5th Symphony is, of course, famously a case in point: a misread metronome marking making the difference between out and out jubilation and merely the illusion of such. In other words, a self-styled delusion.

Both the 11th and 12th symphonies are unapologetically programatic, revelling in a cinematic sensationalism that has brought some high-minded critics down on them. In both, batteries of percussion beat out thrilling tattoos with lethal precision. But the drama that runs deep in the 11th, culminating in an ambiguous major/minor alarum of bells to shame even Mussorgsky, sounds like mere bluster, formulaic underscoring, in the 12th.

But then along comes Petrenko to drive that bombast with such anger and disgust that even the unredeemable coda of the finale – protracted tub-thumping as hollow as it is inconsequential – is suddenly a cry of disgust, an admission that the composer had long since abandoned the idea of celebrating Lenin’s idealism with anything other than a heavy heart.

These pieces – and their finest interpreters – are still full of surprises.

BARBICAN: Classical Music Podcasts

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – January 2021

27/01/2021

A Conversation With RUPERT GOOLD & DUNCAN SHEIK: ‘American Psycho’ – A New Musical Thriller

19/11/2013