GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – March 2021

A recent conversation with Vasily Petrenko once again brought home to me just how much at odds our impressions of Russian music can be when shared with those closer to its source. We were discussing his recent pairing of Prokofiev’s Fifth Symphony and Myaskovsky’s Symphony No 21 (the one with the gloriously effusive second subject) with the Oslo Philharmonic on LAWO Classics and Petrenko was launching into one of his fascinating lectures on precisely where and for what reasons these exact contemporaries sat in the eyes of the Soviet establishment.

A recent conversation with Vasily Petrenko once again brought home to me just how much at odds our impressions of Russian music can be when shared with those closer to its source. We were discussing his recent pairing of Prokofiev’s Fifth Symphony and Myaskovsky’s Symphony No 21 (the one with the gloriously effusive second subject) with the Oslo Philharmonic on LAWO Classics and Petrenko was launching into one of his fascinating lectures on precisely where and for what reasons these exact contemporaries sat in the eyes of the Soviet establishment.

Prokofiev’s Fifth (his proudest symphonic achievement) marked the composer’s return to Mother Russian after exile and directly or indirectly (depending on your viewpoint) celebrated the hard-won and costly victory which brought the Second World War to a close. No one would argue that it is indeed an heroic piece – not least that first movement with its ice-breaking climaxes. But where I tend to view it in abstract terms Petrenko hears a more sociopolitical narrative with busy bureaucrats in the scherzo and the mechanistic rebuilding of a new society in the finale. Where the infamous coda of that movement is suddenly reduced to gibbering solo strings Petrenko hears madness and mayhem.

My own theory as to why Prokofiev (once such an enfant terrible) was able to leave and then return to the Soviet Union without being targeted by the establishment as relentlessly as was Shostakovich has everything to do with the abstraction of his music when compared to that of his celebrated younger contemporary – its transparency and emotional directness such as one finds in the slow movement of the Fifth where iridescent high romanticism is for me a return to the balletic extravagance of Romeo and Juliet and for Petrenko a nocturnal interlude of his projected but never completed Pique Dame ballet.

But then Prokofiev’s guard came down in what for me is the greatest of the symphonies – the dark and searching Sixth (coming soon from the same Oslo source), the flip-side of the triumphant Fifth – and this time its no-holds-barred oppressiveness did not escape the scorn of the establishment albeit somewhat mollified by the enthusiasm of the critics. Prokofiev pulled no punches in weighing the heavy price of victory against the victory itself and its final twist, where the rhythms of folk dancing morph into bone-crushing goose-steps, was as shocking then as it is now. Nothing ambiguous about it. Me and the Russian definitely see eye to eye on that.

Petrenko is now, of course, an honorary Scouser on account of his lengthy association with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic but he is passionate about what he refers to as ‘cultural integration’ wherever he finds himself. And that will soon more often than not be London at the helm of Tommy Beecham’s old orchestra, the Royal Philharmonic. Such an intriguing prospect for all kinds of reasons – not least his penchant and affinity for British music.

I remind him how I cheekily slipped in a reference to Beecham’s classic recording of Rimsky’s Scheherazade (how prophetic) when I presented one of his earliest UK concerts with the BBC Philharmonic for Radio 3. The reference didn’t go unnoticed but at the time he was rather more preoccupied with retaining his dignity when the button on his trousers popped just before making his entrance. Tempi were probably brisker that day.

You May Also Like

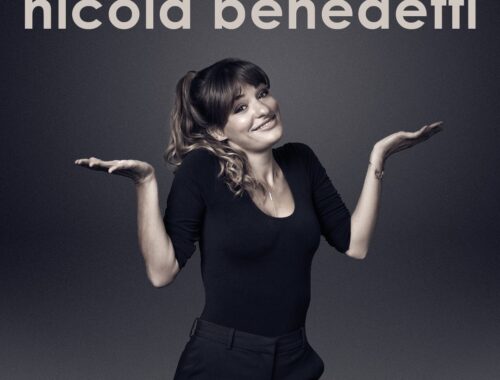

A Night in with NICOLA BENEDETTI

04/02/2021

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – July 2018

17/07/2018