GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – March 2019

In preparation for a public encounter with the astute and ever-enquiring Vladimir Jurowski on the subject of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen my mind goes back to the first time I saw the film of Patrice Chereau’s celebrated Centenary production at Bayreuth and the realisation that truth in drama goes way beyond concepts and visual metaphors and resides in a place where an actor’s face reveals what is in their soul at that particular moment in time. Chereau’s Ring was the first operatic film that I had seen where the unforgiving scrutiny of the camera was not an embarrassment for any of the singers in that extraordinary cast (and let’s face it, the physical effort of singing is not as a rule something to be viewed in close-up) but rather a total vindication of Chereau’s probing and exhaustive work with them.

In preparation for a public encounter with the astute and ever-enquiring Vladimir Jurowski on the subject of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen my mind goes back to the first time I saw the film of Patrice Chereau’s celebrated Centenary production at Bayreuth and the realisation that truth in drama goes way beyond concepts and visual metaphors and resides in a place where an actor’s face reveals what is in their soul at that particular moment in time. Chereau’s Ring was the first operatic film that I had seen where the unforgiving scrutiny of the camera was not an embarrassment for any of the singers in that extraordinary cast (and let’s face it, the physical effort of singing is not as a rule something to be viewed in close-up) but rather a total vindication of Chereau’s probing and exhaustive work with them.

These mythical characters with their human aspirations were at last recognisable to us as much more than cyphers and caricatures, heroes and villains, and when at the close of Götterdämmerung Valhalla went up in flames and the Gibichung people looked quizzically out into the auditorium we were effectively looking at ourselves and contemplating all that we have seen and learned on this epic journey. Chereau’s staging was greeted with dismay and derision on its first outing because it dared to break the mould of tradition and to look long and hard at the motivation behind each and every character, to examine their motives – however primitive – and to clarify their reasons for being.

Wagner, by his own admission, was seeking to create an entirely new kind of music drama, one which the poetic, visual, musical and dramatic arts coalesced. But there can be no drama without emotional truth, however brilliant the stagecraft, and that has been the challenge of every director who thought themselves equal to the herculean task. I remember once talking to the great Richard Jones about his notoriously controversial Ring for the Royal Opera in 1993 and at one point during the conversation he all but confessed that in moments of doubt he had often wondered if he should have steered clear of the piece altogether such was his distaste of so many of its characters and the compulsive need he felt to belittle them, to bring them down to size.

It has often been said that the definitive production of the Ring exists only in our imaginations. You might say that’s the easy way out and something of a cliché – but it also explains why ‘stripped-back’ semi-stagings such as Opera North embarked upon from 2012-2016 and Jurowski is currently part way through realising with the London Philharmonic have proved so successful and fulfilling. Because the reality is that Wagner’s tetralogy is so miraculously self-contained, its words and music and the proportions of its drama so perfectly conceived that the aural experience of it can be as thrilling as any theatrical realisation.

The subliminal effect of the Ring’s complex network of leitmotifs means that even the untrained ear can make those all-important dramatic connections and carry the emotional memory of them forward from moment to moment, scene to scene, act to act, opera to opera. And when that ‘redemption of love’ motif so radiantly returns like a benediction at the end of Götterdämmerung it is ‘closure’ in the best sense of the word.

Sometimes hearing is believing.

You May Also Like

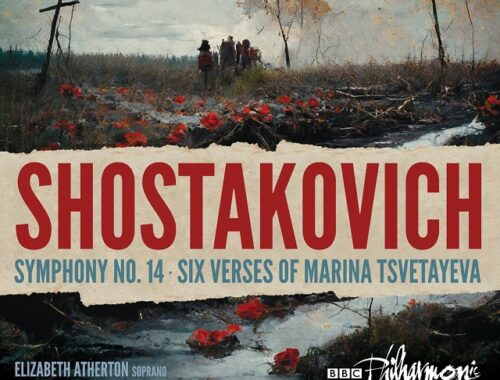

GRAMOPHONE Review: Shostakovich Symphony No 14/Six Verses of Marina Tsvetayeva – BBC Philharmonic/ Storgards

02/10/2023

A Conversation With GIANLUCA MARCIANO: Italian style and traditions

15/10/2013