GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – June 2022

This being the last of these columns for the time being, I thought I’d reflect some more on the issues that keep me and my colleagues so exercised from month to month: the art of realisation, recreation, interpretation, call it what you will. Leonard Bernstein once gently chided me about my ‘dishonourable’ profession asking if it really mattered so much that Karajan makes a ritard at bar 35 in the first movement of such and such a piece where as Furtwängler in his 1953 recording – the live one not the studio version, mind – does not? ‘How do you guys do it?’, he said. Perhaps he should have said ‘why do you guys do it?’ Because the choices that the great and the good make when striving to get into the head of composers great and small and bring those precious notes off the page and into the hearts and minds of their audiences are many and varied.

This being the last of these columns for the time being, I thought I’d reflect some more on the issues that keep me and my colleagues so exercised from month to month: the art of realisation, recreation, interpretation, call it what you will. Leonard Bernstein once gently chided me about my ‘dishonourable’ profession asking if it really mattered so much that Karajan makes a ritard at bar 35 in the first movement of such and such a piece where as Furtwängler in his 1953 recording – the live one not the studio version, mind – does not? ‘How do you guys do it?’, he said. Perhaps he should have said ‘why do you guys do it?’ Because the choices that the great and the good make when striving to get into the head of composers great and small and bring those precious notes off the page and into the hearts and minds of their audiences are many and varied.

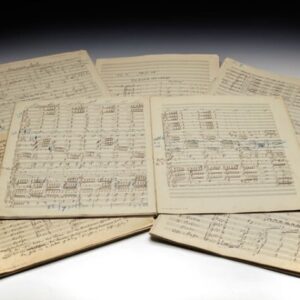

Interpretation is a mighty big word; and regardless of how you view recordings – as a document for posterity or simply a snapshot of a performance at any given time – they make for fascinating comparisons. Musicians will often tell you ‘I only do what it says in the score’ – indeed one conductor said just that to me recently when I complimented him on a particular performance. But we all know that it is far more complicated than that. There is the musicians’ own personality and temperament for starters – the likes of Karajan and Bernstein changed the way the air moved in the room on their walk to the podium alone – and those elements can dramatically impact upon how they respond to what is written in the score: their nose for characterisation and atmosphere and all the other intangibles that lie between the notes. Our response to that – be it from a professional or layman’s perspective – is entirely subjective, of course, but our job in these pages is to share our experience as listeners in such a way as to relive it for the reader in our words.

Some composers – like Gustav Mahler, for instance – could hardly be more explicit in their directions to the interpreter – but the extent to which a conductor (and players) take him at his word makes for much divergence and disagreement. Some try to temper the extremes, the abrupt changes in tempo and dynamics and the like, others take greater risks or simply think they know better as to what is possible and what is not. Even legends like Otto Klemperer (who conducted the offstage band under Mahler, for heaven’s sake) can be notoriously cavalier in their approach to the written score. For the record, Klemperer pretty much ignores most of the aforementioned elements in the first movement of his famous recording of the Resurrection Symphony. Now there’s a one-tempo view of that movement if ever I heard one. But at the time of its arrival there wasn’t a whole lot to compare it with and the piece itself (in decent sound for the first time) swept all before it.

Make no mistake, comparative reviewing is fraught with intrigue and imponderables and we the reviewers have only the confidence in our own musicality and experience to carry our judgements on to the page and into our readers’ imaginations.