GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – January 2018

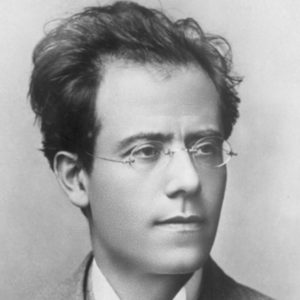

Reviewing Daniele Gatti’s new recording of Mahler’s Second Symphony (see the December issue) I found myself questioning yet again how it is possible to keep this now familiar music sounding startling and fresh and at the very edge of possibility when great orchestras have the facility, the virtuosity, to make light of its super-challenging demands. The Classical and Early Music repertoire returned to instruments of their respective periods to rekindle that “shock of newness” – and indeed through the reassessments of conductors like Roger Norrington Mahler has, too. But Mahler was effectively already writing for a 21st century orchestra when he reimagined the symphony – and above and beyond their sonic demands it still behoves Mahler’s interpreters to heed his very explicit directions – technical and expressive – and never under any circumstances to short-change him. It cannot be said often enough that he he must be taken at his word.

Reviewing Daniele Gatti’s new recording of Mahler’s Second Symphony (see the December issue) I found myself questioning yet again how it is possible to keep this now familiar music sounding startling and fresh and at the very edge of possibility when great orchestras have the facility, the virtuosity, to make light of its super-challenging demands. The Classical and Early Music repertoire returned to instruments of their respective periods to rekindle that “shock of newness” – and indeed through the reassessments of conductors like Roger Norrington Mahler has, too. But Mahler was effectively already writing for a 21st century orchestra when he reimagined the symphony – and above and beyond their sonic demands it still behoves Mahler’s interpreters to heed his very explicit directions – technical and expressive – and never under any circumstances to short-change him. It cannot be said often enough that he he must be taken at his word.

I remember a rather distinguished conductor once saying to me in an interview that he believed Mahler’s excesses required tempering, that certain awkwardnesses (that was the word he used) relating to his wildest fluctuations of tempo and dynamics needed a degree of adjustment to make them practicable and credible. But Mahler traded in the incredible. He took all the trappings of 18th and 19th century Austro-German music and pushed them to the nth degree. Everything was writ large, larger, largest. The sound of silence and the threshold of pain were achieved in dynamics, accelerandos were reckless sprints to the cliff edge, ritardandos anticipated hugely rhetorical pronouncements, general pauses opened up great chasms in the superstructure. The drama was, and still is, in the excess.

But the conductor not mentioned by name above was far from being alone in his misapprehension. In what is generally regarded as a landmark recording of the Second Symphony no less a figure than Otto Klemperer fashioned an account where the all-important first movement chose largely to ignore Mahler’s huge diversity of tempo and the drama ignited therein. Klemperer’s first movement was/is pretty much one tempo with Mahler’s strategically planted tactical shocks all but ironed out. And yet Klemperer conducted the offstage band in one of Mahler’s own performances of the Second. You’d have expected something that came directly from the horse’s mouth. Wouldn’t you?

In a subsequent conversation I had with Riccardo Chailly about this contentious first movement he made the very valid point that its first draft – Totenfeier – (which Klemperer will have seen) is devoid of instruction. Was Klemperer taking his cues from that? Perhaps. But the real drama resides in the very specific directions that Mahler added to the finished movement. There is that monstrous pile up at the climax of the development which is chronicled to accelerate into a battering sequence of dissonant chords. If you know the piece you’ll know the place. There is no ritardando into that chord sequence (as most conductors instinctively apply) but a sudden and crushing molto pesante which by its very weight should grind the tempo almost to a halt. Taken literally – as only one or two in my experience have – the effect is jaw-dropping. As I say, it’s all about taking Mahler at his word.