GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – December 2020

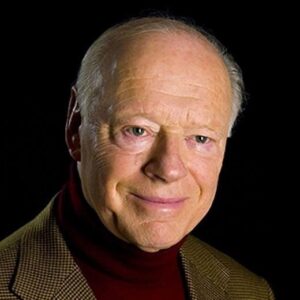

Like many I was thoroughly absorbed by John Bridcut’s touching film about Bernard Haitink – The Enigmatic Maestro. Not entirely sure about the title because what you see is surely what you get with Haitink: a decent, compassionate, and painfully shy maestro whose legendary status in this so often ego-driven profession is almost a contradiction in terms. I think Bridcut was right to highlight Anton Bruckner in Haitink’s pantheon of favourite composers. Spiritually, temperamentally, they have so much in common: patience, humanity, and an all-embracing belief. In so many (or few) words, Haitink expressed how much he had grown into this music, how far he had come with it from the firebrand and, yes, more interventional conductor he was in his youth.

Like many I was thoroughly absorbed by John Bridcut’s touching film about Bernard Haitink – The Enigmatic Maestro. Not entirely sure about the title because what you see is surely what you get with Haitink: a decent, compassionate, and painfully shy maestro whose legendary status in this so often ego-driven profession is almost a contradiction in terms. I think Bridcut was right to highlight Anton Bruckner in Haitink’s pantheon of favourite composers. Spiritually, temperamentally, they have so much in common: patience, humanity, and an all-embracing belief. In so many (or few) words, Haitink expressed how much he had grown into this music, how far he had come with it from the firebrand and, yes, more interventional conductor he was in his youth.

The paradox, of course, is that however much a conductor wants to believe that music is an entirely communal pursuit, a shared experience (and ultimately, of course, it is), you do not rise to the very top of the maestro tree without a high degree of self-belief in the musical choices you make and ask others to share. Every conductor has a view and to suggest that a conductor like Haitink simply gets out of the way and lets the music speak for itself is a mistaken one in my opinion.

I have never shared the enthusiasm for Haitink’s ‘view’ of Mahler or Shostakovich, for instance. I’ve always felt he was temperamentally unsuited to both. And whether or not one shares his ‘objective’ view of Mahler the reality is that Haitink has always chosen to minimise the discomforting extremes in which his scores abound. This is not my opinion, it’s there in black and white in the scores. Why would Mahler write ‘schnell’ so emphatically over the final bars of the first movement of the Third Symphony if what he really wanted was for the tempo to remain the same throughout the final pages? Just one of countless examples of what one might describe as ‘neutering’ that I took away from Haitink’s rapturously received Prom performance of the piece in 2016.

There was a very revealing moment in Bridcut’s film when Haitink suggested that in the autumn of his life his inclination was to give Mahler a wide berth. ‘It’s all so loud’, he said, or words to that effect. And it brought to mind an off-the-cuff reaction he gave to Roger Norrington’s first ‘period’ Beethoven Symphony recordings which I overheard during a break in one of his recording sessions. I remembering him screwing up his face and shaking his head disapprovingly: ‘All trumpets and drums!’

But then Haitink would be the first to acknowledge, even gently mock, his own ‘conservatism’. His open disapproval of Richard Jones’ infamous staging of Wagner’s Ring during Haitink’s tenure at the Royal Opera House (highlighted in the film) was nonetheless tempered with respect for its intellectual rigour – and when I interviewed Haitink for the Wagner Society shortly after its opening he made a point of telling the audience that we had not gathered to ridicule the production but to address the questions it posed and, more importantly, to talk Wagner. When I gently asked him what his production might be like if he were to stage the Ring, he thought for a moment and said: ‘Very boring’. Modesty and self-deprecation – so typical of the man