GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – April 2021

It has often been said that over the last half-century or so orchestras have begun to sound more and more alike. As the instruments themselves have grown in sophistication, evolved to be more flexible and capable of greater nuance and sonority, indeed greater volume, so certain idiosyncrasies we came to know and love – like, for instance, the heavy vibrato of Russian brass – have become less pronounced, indeed in some cases vanished altogether. Different ‘personalities’ still exist, of course – the character of an orchestra is something else, something which comes from style and to a great extent the choices made by Chief Conductors and Music Directors.

It has often been said that over the last half-century or so orchestras have begun to sound more and more alike. As the instruments themselves have grown in sophistication, evolved to be more flexible and capable of greater nuance and sonority, indeed greater volume, so certain idiosyncrasies we came to know and love – like, for instance, the heavy vibrato of Russian brass – have become less pronounced, indeed in some cases vanished altogether. Different ‘personalities’ still exist, of course – the character of an orchestra is something else, something which comes from style and to a great extent the choices made by Chief Conductors and Music Directors.

In the February issue I extended a warm welcome to Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s coupling of Rachmaninov’s First Symphony and Symphonic Dances – an absolute blinder of a disc rejoicing in the Philadelphia Orchestra’s long and intimate association with the composer who not only conducted them but had their sound in mind when he composed his Third Symphony and orchestral swan song, the Symphonic Dances. No one would claim that that sound has not changed since the days of Eugene Ormandy. His choices with respect of balance and colour was decidedly string-led. Nézet-Séguin speaks of the string sound now more in terms of its darkness than luxuriance. And that deep saturating quality undoubtedly prevails albeit leavened now with a sharper rhythmic profile reflective of the young French-Canadian’s dynamism.

So tradition is a big factor. The flexibility and luminosity of the Vienna Philharmonic string sound is a case in point, a way of phrasing passed from generation to generation. The wide-bore horn sound – the Viennese ‘pumpenvalve’ horn – is unique, too, more of a ‘spread’ sonority better able to blend and lending added sheen to the strings (especially cellos) but reaching fortissimo earlier and thus sounding more pronounced. Likewise the reedy oboe sound. Indeed ‘the Vienna sound’ is distinct enough to merit the claim – and that is something the orchestra strives to preserve. One wonders if it might be another reason why they choose not to engage a permanent Music Director or Chief Conductor. Heaven forbid anyone should decide to mess with traditions directly related to the instruments they still play.

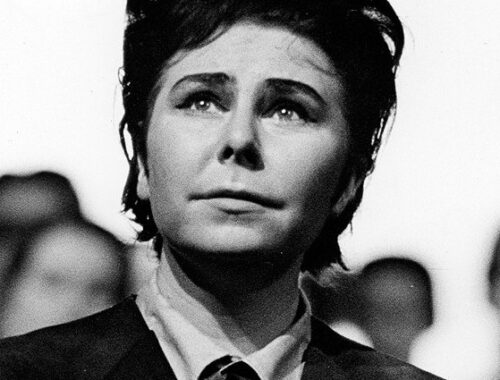

As I write this I am reminded of a somewhat prickly encounter I had with the late Kurt Masur when I interviewed him in New York in 1997. He was bedding in as the orchestra’s music director and I was trying to gauge from him the extent of what one might call ‘culture shock’ of moving from his long-held position at the helm of the Leipzig Gewandhaus (where things ‘hurried slowly’ and old values prevailed) to the rather more dynamic temperament of the New Yorkers. Leipzig’s mellowed venerable sound contrasted with the brighter bigger-boned New York Philharmonic. The comparison interested me, not in terms of a value judgement (which is how Masur read my question; he had been badly briefed – I was not a tabloid journalist) but rather as a practical one taking account of the difference in dynamics between the two orchestras and the adjustments necessary to accommodate them. The reality was that a fortissimo in New York would be heard all the way over in Leipzig – but most certainly not the other way around.

I never did get an answer to the question.

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – July 2021

27/07/2021

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – February 2020

26/02/2020