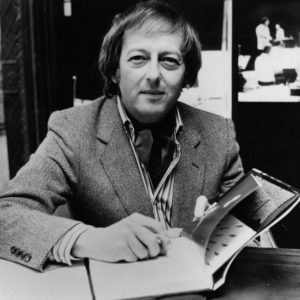

GRAMOPHONE: André Previn – A Tribute

‘You’ve kept those of us who grew up in the same years feeling young; you’ve kept those older than you correctly infuriated, and you’ve been a lighthouse of consistency…We depend on you and love you and trust you…’ Those words were André Previn’s about Leonard Bernstein – but, as Bernstein’s daughter Jamie reminded us when Previn left us in February, they could so easily have applied to Previn himself. Parallels between these two musical giants are as unavoidable as they are odious, of course. They were very different animals. But their completeness as musicians, their ability to embrace and cherish music of spectacularly diverse genres, their connection with popular culture, their many and varied gifts as conductors, composers, pianists, and impossibly eloquent commentators make them kindred spirits in so many respects.

‘You’ve kept those of us who grew up in the same years feeling young; you’ve kept those older than you correctly infuriated, and you’ve been a lighthouse of consistency…We depend on you and love you and trust you…’ Those words were André Previn’s about Leonard Bernstein – but, as Bernstein’s daughter Jamie reminded us when Previn left us in February, they could so easily have applied to Previn himself. Parallels between these two musical giants are as unavoidable as they are odious, of course. They were very different animals. But their completeness as musicians, their ability to embrace and cherish music of spectacularly diverse genres, their connection with popular culture, their many and varied gifts as conductors, composers, pianists, and impossibly eloquent commentators make them kindred spirits in so many respects.

I often wonder if Previn’s transition into the rarefied world of classical music would have been quite as seamless had the ‘Hollywood Years’ not prepared him so thoroughly. The pressure of writing and editing scores, making and supervising arrangements, and conducting them – all whilst under the tyranny of the contract system – made brilliant all-rounders of all those who laboured under it. The old maxim ‘do you want it good or do you want it Tuesday?’ was no joke. It needed to be good and it needed to be delivered on Tuesday.

In one of my interviews with Previn I remember complimenting him on his score for the movie Elmer Gantry with Burt Lancaster and Jean Simmonds. It was tough and strident and innovative – just strings and brass. And he smiled wryly and said: ‘Ah, that must have been the week I discovered Hindemith’s Music for Strings and Brass’. He wasn’t just being self-deprecating, he was explaining how he and his colleagues kept things ‘interesting’ in Hollywood, how cross-fertilisation with the classical world kept the bigger picture alive for them. He revered the work of seasoned Hollywood orchestrators like Conrad Salinger and the debt they owed to 20th century classical greats. His own Oscar-winning work on Lerner and Loewe’s Gigi and My Fair Lady, to say nothing of the Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess were testament to the sound he could and would coax from an orchestra.

And there was something else. We knew him as an exceptional pianist – but he was a great Jazz pianist and on disc he memorably dusted down the two much-loved Lerner and Loewe scores mentioned above and in the cool company of ‘Shelley Manne and Friends’ took them on a voyage of improvisation and rediscovery. They say that out of the greatest discipline comes the greatest freedom – well, Previn was proof conclusive of that truth. The spirit of improvisation was alive and well in every piece he conducted, indeed every phrase he attended as a musician.

His ‘arrival’ as a classical conductor could hardly have been better timed. He and the London Symphony Orchestra ‘found’ each other at precisely the right moment. And they were made for each other. Coming from Hollywood he instantly recognised their extrovert nature and rejoiced in the fact that – and this was his assessment – the LSO were every bit as accomplished sight-readers as any Hollywood studio orchestra. That was really saying something. But it made for super-efficiency in the highly pressurised world of London musical life.

He and the orchestra made plenty of headway fast. They started as they meant to go on. Imagine record company executives today endorsing debut recordings of Walton’s First and Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphonies (neither were especially core repertoire back then)? The former was and still is an absolutely stonking performance. When Simon Rattle came to record the piece some years later he said ahead of the sessions that there was one version ‘none of us’ would ever come close to challenging. He was right.

There was something about Walton that chimed with Previn – the edgy (jazzy) angularity, the capricious manner, and dreamy (that favourite marking sognando) romanticism. It was such a good fit. But so was a great deal of English music – most especially Vaughan Williams. He was so in tune with its very particular sensibilities. It wasn’t just the filmic quality, it was something more, an inner radiance that shone from performances like that of the Bunyanesque Fifth Symphony (which, incidentally, I remember choosing in Radio 3’s Building a Library).

Previn chose his repertoire very judiciously. He knew instinctively what he did well and what, temperamentally speaking, he should avoid. His approach was direct, unfussy (that practical Hollywood efficiency paid dividends) and, in the best sense, non-interventionist. There is surely no better recording of Prokofiev’s complete Romeo and Juliet on disc, nor for that matter Messiaen’s Turangalila Symphony. Iridescent, both of them. Listen to those recordings now and one is reminded what an astonishing array of top-flight soloists occupied the first chairs of the LSO back then. I’m thinking especially of Maurice Murphy, the first trumpet.

As a composer Previn was a comparatively late developer where his concert music and opera was concerned. It still surprises me that he never truly cracked musical theatre – his shows Coco and The Good Companions did nothing to advance or redefine the genre in the way that Bernstein’s musicals did. But I still have a lot of time for A Streetcar Named Desire even if I think that the play belongs more in the vernacular and that his musicalisation of it veers too steeply towards ‘contemporary opera’.

The many tributes to Previn on this side of the pond have all cited or directly quoted his memorable appearance on the Morecambe and Wise show. But Previn was only on that show because he was already a classical music pop-star. His charm, erudition and wit were sharpened by his youth, his Beatles haircut, his trendy 60s polo-neck shirts. He and the LSO abandoned stuffy formality and moved with the times. Classical music was young again.

But unlike the desperation that underscores attempts to ‘popularise’ classical music these days Previn never compromised his musical integrity. On the contrary, he sought to challenge his audiences introducing new and/or neglected repertoire and championing pieces like Rachmaninov’s Second Symphony which he and the orchestra took all over the world and turned from a rarity into a justly lauded piece of core repertoire. I’ve still never heard anyone believe in that piece as he did.

Nor did he ever talk down to his audiences. He used popular culture – namely Television – to introduce audiences to the music he loved and he did so in his own inimitable way. To say that his TV show Music Night would be inconceivable today is a terrible indictment on where we are at. You don’t reach people with compromises, with gimmicks, with installations or video screens or even wet T-shirts – you reach them with a passion and belief in the art form you love and practice. Like Bernstein, Previn was a hugely persuasive commentator and his dry wit and skills as a raconteur were huge attributes in promoting the cause of music.

I remember arriving for one interview flustered and a few minutes late having travelled across London from an especially remote recording session and as I pulled out my sheaf of notes he totally defused the situation by quipping ‘Are those the questions or the directions?’

My colleagues will attest to the fact that many of his more outrageous stories were not for public consumption – but one will suffice to illuminate the immense journey he took from La La Land to the London Symphony and beyond. When he conducted his first Beethoven 9 in London he decided to invite some of his Hollywood cronies as a celebration of the occasion. At the close of the performance when the audience was going nuts (his word) as they do with that piece, one of his Hollywood friends turned to another and said words to the effect of: ‘Wow, will you listen to that! Amazing! I’m so thrilled for André. It’s just such a shame he had to fuck up his career to get here.’

You May Also Like

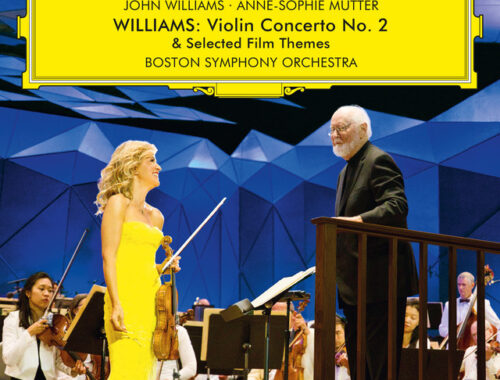

GRAMOPHONE Review: John Williams Violin Concerto No 2 & Various – Mutter, Boston Symphony Orchestra/Williams

20/07/2022

DAME JANET BAKER in conversation: Champs Hill

08/08/2022