Gounod “Faust”, Royal Opera House

“This is my domain”, says Méphistophéles, and suddenly we his audience are behind the footlights looking into an auditorium just like ours. It isn’t a particular original idea casting the devil as master of ceremonies and purveyor of dreams and nightmares but in David McVicar’s thrillingly opulent 2004 staging of Gounod’s Faust the conflict between damnation and salvation sets theatre and church in dramatic juxtaposition with Charles Edwards’ imposing design opening up the dark recesses between a crumbling proscenium and lowering organ loft. Méphistophéles is temporarily in charge, of course, and it’s one hell of a cast he’s assembled to join him and his entourage of fallen angels for this latest revival.

There is Faust himself signing over his soul like credit protection insurance (no compensation for him), his youth and virility restored in the person of the explosively dynamic Vittorio Grigolo. The huge impression he made last year in another French opera – Massenet’s Manon – is only partly reaffirmed here with his powerful middle-voice used to less seductive effect with fewer subito shadings in mezza voce. He’s putting the voice under more and more pressure and it’s surely a tell-tale sign that the high C of his Romance in the third act was, by necessity, pushed in full-voice rather than caressed in head-voice. He’s not the first and won’t be the last to miss the point of that moment. But there’s no denying his vocal and physical charisma – I just wonder how long he can go on singing like this.

Angela Gheorghiu grows more lyrico spinto with every performance with the big money notes now flung out with often startling panache. But she was all over the place in the “Jewel Song” playing fast and loose with tempo and rhythm and causing no end of anxiety for the excellent conductor, Evelino Pido.

No such issues with Dmitri Hvorostovsky’s Valentin – expensive casting but value for money and then some in the resolutely long lines of his showstopping aria. And the devil himself? From the moment René Pape appears, waving sulphurous smoke away from his face, his is an enticingly nonchalant malevolence, booming bass authority offset by melting head tones and many a vocal shrug.

And his and McVicar’s star turn – the diabolical Walpurgis Night ballet – is still a sensation turning decorative divertissement into malevolent mockery. It’s every pregnant woman’s worst nightmare and most definitely Marguerite’s moment of truth.

You May Also Like

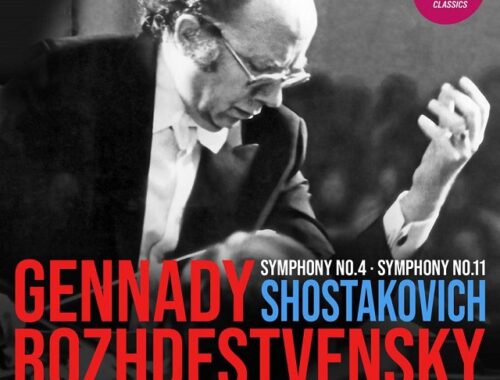

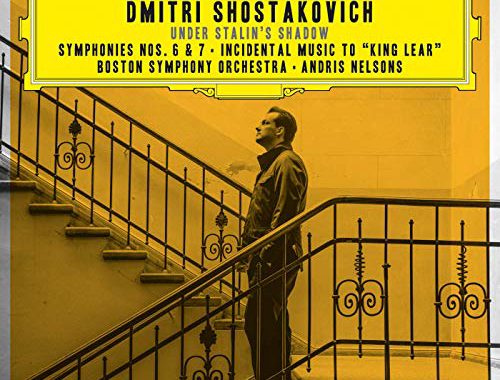

GRAMOPHONE Review: Shostakovich Symphonies Nos. 6 & 7, Etc. – Boston Symphony Orchestra/Nelsons

24/04/2019

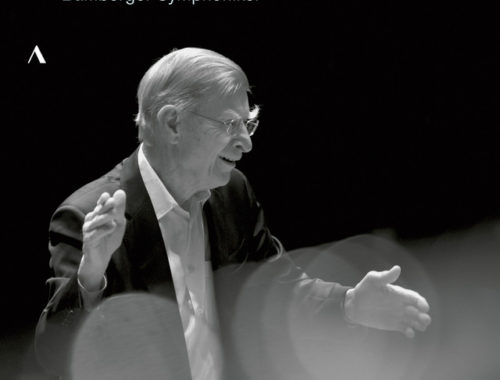

GRAMOPHONE Review: Mahler Symphony No. 9 – Bamberg Symphony Orchestra/Blomstedt

12/09/2019