Flowers for Mrs Harris, Crucible Sheffield

You emerge from Flowers for Mrs Harris a little richer, a little lighter, a little more hopeful. Paul Gallico’s enchanting fable is about many things – it’s about new beginnings, rebirth; it’s about aspiration; it’s about the perception of beauty which belongs to us all; and most of all it’s about kindness, pure and simple, and the notion that what goes around comes around. Richard Taylor and Rachel Wagstaff’s beautiful musicalisation is the kind of piece that should be gracing programmes like the Royal Opera’s for new writing in music theatre but never will because someone somewhere has decreed that “contemporary opera” belongs only to a hardcore of contemporary composers who write music that sounds a certain way and plays to a certain crowd. And yet Flowers, it could be argued, is more opera than musical (as if that matters) and in its beauty and sophistication and sheer open-heartedness draws us all in.

You emerge from Flowers for Mrs Harris a little richer, a little lighter, a little more hopeful. Paul Gallico’s enchanting fable is about many things – it’s about new beginnings, rebirth; it’s about aspiration; it’s about the perception of beauty which belongs to us all; and most of all it’s about kindness, pure and simple, and the notion that what goes around comes around. Richard Taylor and Rachel Wagstaff’s beautiful musicalisation is the kind of piece that should be gracing programmes like the Royal Opera’s for new writing in music theatre but never will because someone somewhere has decreed that “contemporary opera” belongs only to a hardcore of contemporary composers who write music that sounds a certain way and plays to a certain crowd. And yet Flowers, it could be argued, is more opera than musical (as if that matters) and in its beauty and sophistication and sheer open-heartedness draws us all in.

Richard Taylor writes an altogether different kind of musical in which “songs” rarely arrive fully formed but rather are in the process of evolving – beginnings of songs which are content just being songful and serving as aides-memoires, melodic remanants which in some cases return again and again with all their emotional memory intact. Wagner called them leitmotifs. Mostly they live in Taylor’s tiny orchestra (a lushly managed, piano-led ensemble of ten) which is in some ways the most important character of all. Our own emotions ride on its generosity of spirit and it seems to mirror not just what the characters in the drama are feeling but what we are feeling, too.

Taylor understands the music of words, how singing is the natural progression of speaking, and more importantly how character is defined through the very particular nature of individual vocal lines. When Mrs Harris first spies the iridescent organza Dior dress in Lady Dant’s closet and something momentous unlocks inside her, Taylor marries Clare Burt’s thrillingly earthy chest tones to Rebecca Caine’s radiant soprano and together they share rapture from utterly different parts of the vocal spectrum but the same centre of emotion. Every character here has its own sound just as every voice has its own timbre (this can be such a curse of contemporary musicals and opera) and that distinction is carried forward to the Paris of act two where Daniel Evans’ cast double with an entirely new set of characters.

The glory of Evans’ staging is in his pitch-perfect casting with major talents like Anna-Jane Casey (Violent Butterfield/French Charlady) and Laura Pitt-Pulford (Pamela/Natasha) complementing each other so tellingly. When I speak of Taylor’s vocal texture I hear David Durham’s resounding baritone (Major/Monsieur Armand) offsetting Louis Maskell’s lovely lyric tenor (Bob/Andre) and Rebecca Caine’s Straussian soprano. It’s that thing in music of distinctly different timbres making for a euphonious whole. But the most affecting double of all belongs to Mark Meadows who represents Ada Harris’ past and future. When we arrive in our seats to discover Mr and Mrs Harris “at home” in Battersea we have no idea of the stunning coup that is soon to be sprung.

At the heart of Flowers for Mrs Harris, though, is the marvellous Clare Burt back centerstage in a role she might have been waiting all her multi-faceted career for. That it has come at last in such an accomplished piece is a source of great joy for her and us. It’s a wonderful, truthful, moving performance. And it’s a great moment for Richard Taylor, too, with The Go-Between about to open in London’s West End just as Flowers closes in Sheffield. But surely it must have a life beyond Sheffield? I teared up pretty much from the start and remained that way to the finish.

Threepenny Opera, National Theatre

RODGERS REVEALED

You May Also Like

A Conversation With SIR PAUL McCARTNEY: BBC Radio 4 Kaleidoscope

15/09/2015

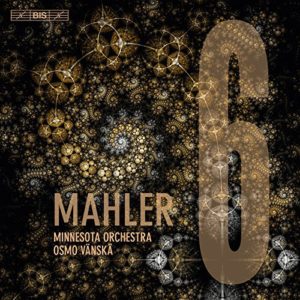

GRAMOPHONE Review: Mahler Symphony No. 6 – Minnesota Orchestra/Vanska

20/06/2018

2 Comments

William Hill

Sorry to have missed it. Do you know if it is going to have an afterlife?

Edward

I sincerely hope so, William. Daniel Evans is going to Chichester….