Dialogues des Carmélites, Royal Opera House

Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmélites is a special and very particular opera. There is nothing else quite like it. Just as the drama – set to the composer’s own libretto – teeters between fear and faith so too does Poulenc’s score, an extraordinary apposition of austerity and lushness where belief is harmonically consonant, festooned in seraphic harp glissandi and warmly homogeneous middle-voices, but fear is omnipresent in the shadows punctuating the score with a succession of precipitous dissonances and the alien sonorities of instruments like the piano. Robert Carsen’s beautiful staging has somehow imagined these stark contradictions visually, beginning with designer Michael Levine’s blank canvas of a stage (which Jean Kalman lights like one of those dark meditatory Rothko’s – all grey, black and shadow) on which revolutionary turmoil and the inner lives of our God-fearing sisters unfolds like a ballet – figures in a hostile landscape. It sounds coldly abstract but it plays like a highly emotive dream.

Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmélites is a special and very particular opera. There is nothing else quite like it. Just as the drama – set to the composer’s own libretto – teeters between fear and faith so too does Poulenc’s score, an extraordinary apposition of austerity and lushness where belief is harmonically consonant, festooned in seraphic harp glissandi and warmly homogeneous middle-voices, but fear is omnipresent in the shadows punctuating the score with a succession of precipitous dissonances and the alien sonorities of instruments like the piano. Robert Carsen’s beautiful staging has somehow imagined these stark contradictions visually, beginning with designer Michael Levine’s blank canvas of a stage (which Jean Kalman lights like one of those dark meditatory Rothko’s – all grey, black and shadow) on which revolutionary turmoil and the inner lives of our God-fearing sisters unfolds like a ballet – figures in a hostile landscape. It sounds coldly abstract but it plays like a highly emotive dream.

Imagine the restless populace as a pitiless tsunami washing across the stage, leaving a trail of debris, human and otherwise – that is one of Carsen’s recurring images. Sometimes this teeming shoal of humanity (a 67-strong Community Ensemble) is static in the shadows, sometimes it advances on us, the audience, impassive but somehow accusing. Lighting changes are locked into the rhythm and chordal punctuations of the score so the whole show, musically and dramatically, feels organic. But fear is the key, and two wonderful scenes – the death of the Prioress, Madame de Croissy (a no-holds-barred Deborah Polaski), who does not go quietly into the dark night of her soul, and Sister Blanche’s own crisis of faith – mirror what is happening on the streets of Paris. Polaski gives the former a gothic grandiosity while Sally Matthews’ Blanche is a transference of the Prioress‘ terrible doubt in the face of death. The intensity and fearlessness of Matthews‘ performance cannot be denied but the indistinct middle voice might well now be the casualty of her shift to a weightier repertoire where top and bottom are pushed to dramatic effect. Still, commanding, no question, as is Emma Bell as Madame Lidoine displaying faith and vocal resolve enough for all her charges.

Simon Rattle, conducting, so obviously loves this score and what a spell he casts with its wonderfully diaphanous colours and especially rapt pianissimi. The precipitous fortissimi are not compromised, either – so a startling dynamic range – and I loved, too, the way he and the ROH Orchestra and Chorus make no apologies for the sumptuousness of Poulenc’s “religiosity”: the Lazarous and Gethsemane moments were almost indecently gorgeous.

The always upsetting final scene brings the production’s most affecting dramatic coup beginning when the nuns in unison disrobe from their black habits so that their white undergarments shine out from the black mass (in more ways than one) of the crowd. As the Salve Regina soars, now punctuated, violated, by the sound of the guillotine (now we know precisely what Poulenc’s precipitous chords foretold), each of the martyred sisters drop to the floor where their habits lay neatly folded – effectively waiting for their calling – at the start of the evening. A poetic symmetry indeed.

image: DIALOGUES DES CARMELITES PRODUCTION (C) ROH/STEPHEN CUMMISKEY

Miss Saigon, Prince Edward Theatre

You May Also Like

A Conversation With SIR PAUL McCARTNEY: BBC Radio 4 Kaleidoscope

15/09/2015

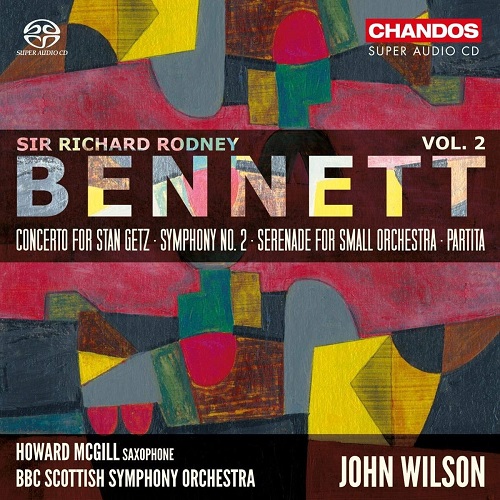

GRAMOPHONE Review: Richard Rodney Bennett Orchestral Works Vol. 2 – BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra/Wilson

15/09/2018