Charpentier “Medea”, English National Opera, London Coliseum (Review)

Hell hath no fury… and in Medea’s case comes so precipitously that even her children must be taken from the room whenever her demons threaten an unscheduled appearance. That is but one of many telling details that trouble the senses in David McVicar’s new staging of Charpentier’s take on the myth at English National Opera – and I shall long be troubled by the sight of those two little boys in their pyjamas clutching on to their mother as the beast in her resolves that the children must die “to serve her hate”. And then the clinching line delivered with such withering relish by Sarah Connolly: “But how sweet when I taste his pain.” He, of course, being their father Jason whose scorn will transfigure her.

The first thing that must be said of this UK stage premiere is that Connolly’s presence in it is its greatest strength. The word “presence” is overused but in her case the voice and manner exude it. Her commitment to each idea, each word (and they are fine, graciously high-flown, words in Christopher Cowell’s translation), each musical inflection has been thought and felt through – and when she is not on the stage you feel her in absentia. Which is just as well given the Charpentier and his librettist’s protracted exposition (two acts of it – and a Prologue which McVicar wisely cuts) which for my money compromises the dramatic balance of the piece and begs our indulgence during the elaborate “entertainment” which brings on the slaves of love and Cupid’s chariot following Medea’s banishment in act two. At least McVicar makes a dramatic point here – that all’s fair in love and war, that indeed love motivates war, and that in his pointed allusion to the 1940s and a war that we can all relate to he has a brilliant opportunity to turn this entertainment into a kind of propaganda drive for that war bringing on a sequined Spitfire and a bevy of leggy female aviators to join high-kicking and kinetically saluting Hollywood sailors (“The Fleet’s In”).

This allusion to the movies is pointed up in the use of studio lights and props and through a central conceit that the location – a royal chateau of 17th century magnificence (designer Bunny Christie) – has been commandeered for the war effort. This shrewdly gives us both a sense of reality in the drama and ample opportunity for McVicar to pay homage to the spectacle of the French Baroque. A reflective floor and mirrored doors play wonderful tricks with the light (Paule Constable) and when Medea summons the daughters of the Styx to her presence and the floor opens to spew up war-weary soldiers now ravaged by what look to be undead Miss Havershams the reflections seem to liquify the set. The choreography (Lynne Page) is pointedly dramatic and pointedly plays against the score’s innate syncopations. It has wit and real physicality and it wrong-foots you.

Christian Curnyn, the conductor, is an enthusiastic advocate of Charpentier’s score (believing it to be perhaps the glory of the French Baroque) and even brought it to the stage for his curtain call – and yes, the way in which swathes of precisely notated sung recitative are as much a natural extension of speech as the numbers are a natural extension of the recitatives is extraordinary. One thinks of how strategically Charpentier places Medea’s aria “Is This What Love is Worth?” (so heart-rendingly sung by Connolly) at the fulcrum of the drama; one thinks of the way recits bloom into aching canons – like the duet between Jeffrey Francis‘ Jason and the lovely Katherine Manley’s Creusa towards the terrible climax of the piece. But there is an awful lot of it (clearly Curnyn and McVicar eschewed the very idea of cuts) and I cannot honestly say that all of it gripped me any more than I can pretend that in a theatre this size the subtleties of instrumental colour weren’t to some extent dissipated before reaching one’s ears. Then again one applauds them – and ENO – for bringing it to us at all.

McVicar’s cast was exemplary. Roderick Williams (Orontes) and Brindley Sherratt (Creon) are such honest and “complete” performers vocally and dramatically and Sherratt’s big number found resonances that went way beyond the vocal. But this is a major triumph for Connolly and as she surrenders her humanity and hurtles towards “transfiguration” in revenge (a throat-catching moment in which her world is literally torn asunder) you almost don’t see the monster for the hurt of betrayal.

Briefly...

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE Review: Jurowski Conducts Stravinsky Vol 1 – Angharad Lyddon, London Philharmonic Orchestra/Jurowski

02/10/2022

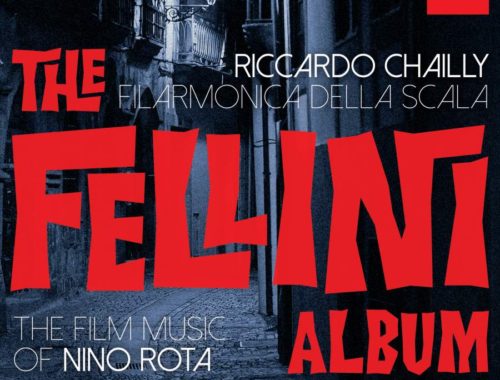

GRAMOPHONE Review: The Fellini Album – The Film Music of Nino Rota, Filarmonica Della Scala/Chailly

14/08/2019