Budapest Festival Orchestra, Hough, Fischer, Royal Festival Hall

The Hungarian Presidency of the EU and the start of the Liszt Bicentennial – two very good reasons for some of Hungary’s (indeed the world’s) finest – the Budapest Festival Orchestra – to party. And bringing Esterhazy to Oxford in Haydn’s Symphony No.92 was as good a way as any for Ivan Fischer’s marvellous orchestra to shine in that very personal way of theirs.

Here’s an orchestra where communication always comes before presentation, where strength of character looks you straight in the eye and invites, no positively insists upon, your attention. In Haydn, elegance bonded with rusticity and geniality with wit. Woodwind solos, keen and articulate, were tweaked to ear-popping effect and the string playing was, well, natural, be it intimate and homespun or skittishly off-the-string. This orchestra is not there to impress, it’s there to make music.

There are few romantic, “golden age”, stylists of Stephen Hough’s calibre around – and even fewer to whom the Hungarians would entrust their Liszt. Hough returned the compliment with a dazzling performance of the 1st Piano Concerto. The temperament of soloist and orchestra was hurled down like a gauntlet in the opening flourishes and thereafter Hough tossed off the fabulous embellishments with that very particular sense of the improvisatory, little turns and throw-away ornamentation beautifully dovetailed into the rubato, the sound always matched to the phrasing. The dreamy slow section was so airy, so translucent, that it hardly seemed possible that this could be the effect of hammers striking strings – but then conversely the barnstorming finale was rhythmically, percussively, a marching band with flashing double-trills and ringing upper-register pyrotechnics. Hough responded to his ovation with more Liszt, late Liszt, this time very short and very quiet – the Andantino from Five Little Piano Pieces.

And then a tree appeared on the stage – just one of the little eccentricities characterising Fischer’s eminently romantic account of Beethoven’s 6th Symphony “Pastoral”. Woodwinds, in their roles as yodelling peasants and assorted bird-life, were now distributed throughout the orchestra, the principals among the first desk strings, their colleagues pulling focus from other directions. The performance was positively Arcadian in its beauty with wonderfully hushed dynamics reflecting Beethoven’s minor key modulations and startling sforzando trills in the second violins suddenly awakening us to the shimmering abundance of it all. And the tree was not struck by lightening in the storm.

Love Never Dies...twice

You May Also Like

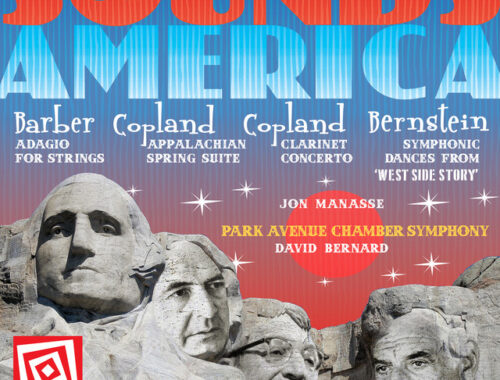

GRAMOPHONE Review: Sounds of America – Jon Manasse, Park Avenue Chamber Orchestra/Bernard

20/12/2021

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – January 2021

27/01/2021