Britten “Billy Budd”, English National Opera

The sight of Kim Begley’s old and broken Captain Vere silently mouthing Billy Budd’s death sentence as it is read out in the final scene of Britten’s opera will be one of the enduring images of David Alden’s new English National Opera production. It’s a terrible mantra that he will repeat over and over and over to the end of his days. “Long ago…many centuries ago”, he recalls. Time is indeterminate, the pain eternal. And as for Vere, so for Alden. 1797 is the date in the ship’s log – but the morality of Herman Melville’s tale is tied to human nature in perpetuity.

It’s hard to determine a precise period or indeed a clear naval identity for Alden’s staging in Paul Steinberg and Constance Hoffman’s designs but the black leather greatcoats and dehumanising uniformity of the rank and file – each a number not an individual – has an ugly familiarity. And bringing the whole piece inescapably closer to us in terms of reference – most of it stylised and non-specific anyway – is Alden’s chosen way. What really tells here is the physical expression, the precisely drilled blockings behaving like a testosterone-fueled ballet where ropes and oil drums (a clear reference to the prize in modern warfare) are sculpted metaphors and the belly of the ship can also act as a monstrous canon into whose barrel we gaze. Steinberg’s set dwarfs its inhabitants, bearing down on them, “containing” them. And is it coincidental that the rusted iron support beams of the mighty hull are fashioned like the Union flag?

But should you quibble (I don’t) with Alden’s decision to remove the piece from its specific time and place you could have no such qualms about the magnificence of the musical presentation. Edward Gardner inspires his fantastic chorus and orchestra to great heights, the surge and swell of Britten’s score as surely caught as its queasy undertow. Bright young stars emerge from the ensemble – Nicky Spence’s vivid Novice, shamed by fear, Duncan Rock’s wonderfully virile and “present” Donald – and experience shines through Gwynne Howell’s Dansker.

The apposition of good and evil, innocence and envy, achieves a startling tension between Benedict Nelson’s open and unforced Billy and Matthew Rose’s indomitably cruel Claggart, his lustful brutality obscenely suggested in the fondling of Billy’s neckerchief. And at the centre of the moral dilemma is Kim Begley’s Vere, the heroic timbre of the voice pointedly draining away in guilt and impotence.

A thrilling company achievement. World class.

You May Also Like

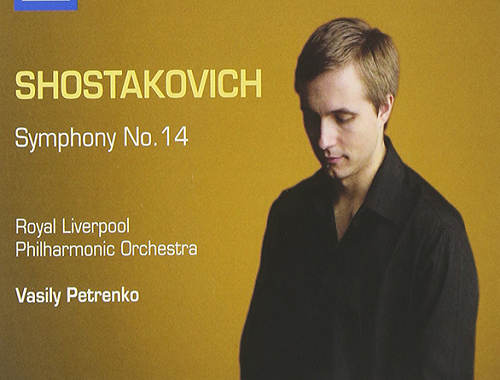

A Conversation With VASILY PETRENKO: Shostakovich’s Symphony No 14

08/02/2014

GRAMOPHONE Review: Jurowski Conducts Stravinsky Vol 1 – Angharad Lyddon, London Philharmonic Orchestra/Jurowski

02/10/2022