Benvenuto Cellini, London Coliseum

Hector Berlioz and Terry Gilliam were undoubtedly made for each other – kindred spirits with wild imaginations, impractical demands, and a touch of anarchy. But Berlioz was a chaotic dramatist at best and in a piece like Benvenuto Cellini which he and his librettists described as an Opéra semi-seria but was in truth a miserable attempt at comedy Gilliam has his work cut out papering over the cracks and riding out the longueurs with increasingly Pythonesque desperation. It is strange, is it not, that Berlioz could compose the tautest and most dramatically coherent of overtures for the piece (well, two actually – Carnival Romain features heavily as well) but so thoroughly lose his way when people not instruments came into the equation?

Hector Berlioz and Terry Gilliam were undoubtedly made for each other – kindred spirits with wild imaginations, impractical demands, and a touch of anarchy. But Berlioz was a chaotic dramatist at best and in a piece like Benvenuto Cellini which he and his librettists described as an Opéra semi-seria but was in truth a miserable attempt at comedy Gilliam has his work cut out papering over the cracks and riding out the longueurs with increasingly Pythonesque desperation. It is strange, is it not, that Berlioz could compose the tautest and most dramatically coherent of overtures for the piece (well, two actually – Carnival Romain features heavily as well) but so thoroughly lose his way when people not instruments came into the equation?

Edward Gardner and the ENO Orchestra despatched the overture with laudable panache, ratcheting up the excitement with almost reckless abandon as we headed into the home strait. It came as no surprise that Gilliam duly storyboarded these latter pages, a tramp pulling newspapers out of the dustbin of history, if you like, while headlines flashed across the front cloth chronicling the stalling of Cellini’s papal commission for a bronze statue of Perseus. It was then that the Roman Carnival exploded into the auditorium, showers of confetti descending from the Coliseum dome and the arrival of giant puppets Lion King-style down the aisles. Though in keeping with that show, the best was now behind us. The first act would tell us how much the self-publicist and rogue Cellini was in love with Teresa (promised, of course, to another) but it would be 90 minutes before the fateful Mardi Gras in the Piazza Colonna brought any theatrical excitement beyond some fanciful romantic diversions and floridly stratospheric singing from the excellent principals, Michael Spyres and Corinne Winters.

Gilliam, of course, had thrived on the eventful narrative and lurid imaginings of The Damnation of Faust – in that his visual imagination and cartoonish humour could run riot – but what to do with these paper-thin caricatures who themselves send-up the genre and with a little help from Charles Hart’s knowing translation repeatedly make sure we are in on the joke. Not a lot, it seems. The action (such as it is) is played out in ink-drawn pantomimic sets (Gilliam and Aaron Marsden) with a touch of Edward Gorey about them. They shift and slide queasily while wacky projections tip things into the realms of Gilliam hallucination in the two climactic scenes – the descent of the Mardi Gras into bedlam and Cellini’s long-awaited redemption with the completion of the statue and the consummation of his love for Teresa.

The music is sporadically – but only sporadically – enchanting with flights of fancy taking the lovers into near-unsingable rapture. There seems to be little that Corinne Winters cannot do in terms of vocal (and physical) agility and her way with line is most seductive. Security and excitement go hand in hand and she belies the difficulties with apparent fearlessness. Michael Spyres is the purveyor of an heroic bel canto that equally seems to fly in the face of the impossible and it was only unfortunate that in his most testing number – his beautiful act two, scene two, aria which is surely the highlight of the entire piece – he was showing signs of fatigue.

A notable impression was made by Paula Murrihy in the trouser role of Ascanio, Cellini’s business manager – real vocal and physical swagger – and Willard White (with a little help from Gilliam’s costume designer Katrina Lindsay) revived memories of Fellini’s Vatican fashion show with his unashamedly camp arrival as Pope Clement VII. A menacing fayness might best describe this papal turn.

The Buffa elements of the opera, though, are much less interesting and bring insane rhythmic difficulties to most of the ensemble in pursuit of the kind of Offenbachish onomatopoeia that the French seemed to find amusing. But the ENO Chorus were as game and heroic as ever and they alone could be said to have justified the revival of this problematic and invariably tedious piece.

Frankly it needs more, much more, than Gilliam could throw at it to make it work – if indeed it ever could.

You May Also Like

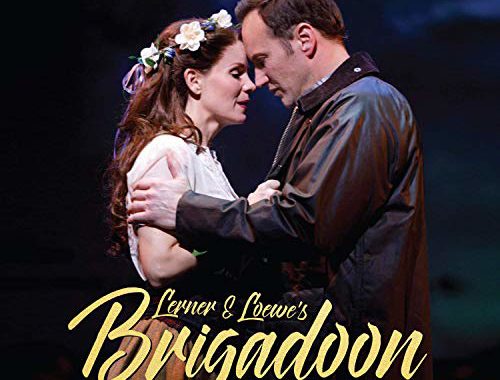

GRAMOPHONE Review: Brigadoon – New York City Center 2017 Cast/Berman

27/03/2019

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – December 2021

10/01/2022