A Chorus Line, London Palladium (Review)

Even singular sensations grow older – yet A Chorus Line, which coined the phrase, seems ageless, so sure is it of its place in musical theatre history, so locked now into our theatrical consciousness. It is, no question, a wonderful show whose fabric of book (James Kirkwood and Nicholas Dante), music (Marvin Hamlisch) and lyrics (Edward Kleban) is seamless and, more importantly, whose vision – as originated by choreographer/director Michael Bennett – has achieved a kind of immortality. Bob Avian, who assisted on the original staging back in 1975, is now the show’s guardian and watching this timely London revival, imaginatively cast and wholeheartedly delivered, you realise that it isn’t just nostalgia that faithfully reproduces it exactly as some of us remember from 1976 but the indisputable fact that as stagings go it’s pretty damn perfect. You don’t dare touch a hair on its well-groomed head; nips, tucks, and facelifts don’t even bear thinking about.

So we will always be – as it says above the blacked-out stage – in that time, 1975, and that place, a Broadway Theatre. And we’ll always get the same buzz when the lights come up on a stage full of dancers in rehearsal clothes (circa. 1970s) and the same jolt when rehearsal piano bows out and the band kicks in. I know it was a first night but I reckon the Palladium will explode every night when that happens. But there’s something else, too. There’s no business like show business, they still tell us, but no business either that celebrates the rejection, the humiliation, the heartache like this business does. A Chorus Line is that weird thing: a bleak show that lifts the spirits of anyone who has ever yearned for their moment in the spotlight and even those of us that merely look on. And as the survivors of the first cull find their place behind that quite literal line on the stage between us and them we stop thinking how convenient it is that all life is here – all shapes, sizes, and personalities – and simply buy into the whole joyously joyless experience.

The intricacy of the staging is breathtaking, the choreographic thrills many and varied – most notably the seemingly unstoppable crescendo of the Montage “Hello Twelve, Hello Thirteen”, a classic of the modern day musical. Again and again we are taken in and out of the dancers’ heads always to return to their place behind that line. When Paul, the elegant gay boy with a woman’s sensibility (excellent Gary Wood) is injured at the very point of likely securing his place in the show the line reforms but, heartbreakingly, with a gap where he once stood. Like all great musicals, a few of Marvin Hamlisch and Edward Kleban’s terrific point numbers would be inexplicable, even unremarkable, out of the context of the show – but there’s one remarkable song, “At the Ballet” which is the essence of the show and encapsulates the need that so many performers have to escape reality.

Ensemble is everything in A Chorus Line and this London cast deliver on so many levels. Of course, some characters will always stand out from the crowd: the tall, imperious, and super-laconic Sheila of Leigh Zimmerman, the feisty Diana of Victoria Hamilton-Barritt who pretty much nails the song about theatrical pretension “Nothing”, and Scarlet Strallen’s terrifically committed and wonderfully danced Cassie, the featured dancer who never quite made stardom and whose failed affair with John Partridge’s authoritative Zach, the director, almost deprives her of the job she so badly needs. No matter how many times you see it, when curved mirrors descend for her big (and how) showstopper “The Music and the Mirror” the multiplication of her fluid form in that iconic scarlet (how apt) dress will always set the pulse racing.

Towards the end of the show when one of the characters says ruefully “Nothing runs forever”, you’re thinking – wrong, A Chorus Line will.

You May Also Like

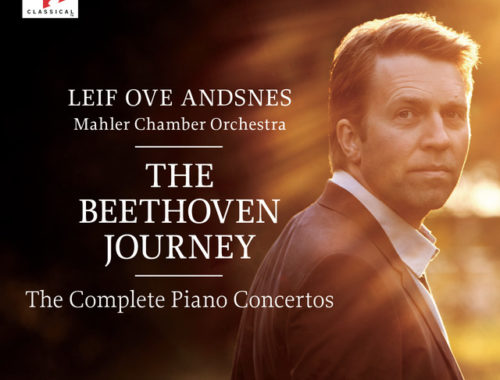

A Conversation With LEIF OVE ANDSNES

01/10/2012

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – December 2019

01/01/2020