TUESDAY 3RD AUGUST 2010 PROM 23: BBC SCOTTISH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA/ RUNNICLES

Royal Albert Hall

Questions may be raised in the Scottish parliament about the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra bringing an all-English programme to the Proms (one dear soul even felt compelled to wave the Scottish flag) but no one is likely to be arguing about the quality of the music making. Predictably Vaughan Williams’ Lark Ascending pulled in a massive crowd but it was the concert opener by John Foulds (a Proms first) that really raised curiosity levels.

Dynamic Triptych can never quite make up its mind whether or not it wants to be a fully-fledged piano concerto. The very able bodied pianist Ashley Wass seemed to be splashing on keyboard colour but little of real pianistic interest for much of the opening movement: a fiery toccata-like romp with pile-driving rhythms and flaring horns. There was an air of filmic underscoring about it (The War of the Roses?) and even the cadenza – a hair-raisingly assertive reprise of the two key thematic elements – didn’t really hint at much beyond out and out rhetoric, albeit with a twist of individuality.

But then a quiet dynamism took hold and the opening rumination of the slow movement found the soloist musing on a perfectly beautiful and searchingly harmonised melody prompting strangely erotic quarter-tone slides from the lower strings. The textural ripeness of the piece now grew rather startling and even the imploding climax of the finale was genuinely unexpected.

Enter, then, Vaughan Williams and not one but two masterpieces: Serenade to Music, where the “touches of sweet harmony” proved more happily suggestive of the blend rather than the individuality of the 16 young soloists; and The Lark Ascending whose songful chirrupings – beautifully inflected by Nicola Benedetti – drew 6000 pairs of ears into its confidence. Space – even one as large as this – truly enhances this piece.

But this sasonac Prom will be remembered most of all for Donald Runnicles’ hugely impressive account of Elgar’s First Symphony. The challenges of this mighty piece – not least the precarious tension between tenderness and tumult – can never ever be underestimated. But Runnicles and the orchestra chronicled its multi-layered narrative with great accomplishment. The transition from blustering scherzo into contemplative slow movement was like a door opening onto an altogether kinder world. Each return to the main theme was more healing than the one before and the clarinet’s final inflection seemed to echo the words of Gerontius’ Angel: “softly and gently”.

SUNDAY 1ST AUGUST 2010 ORCHESTRA OF THE AGE OF ENLIGHTENMENT/ RATTLE

Royal Albert Hall

A night of love; an hour or two of quiet revelations. As Simon Rattle and his period band – the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment – nursed the sensuous, no erotic, harmonies of the love scene from Berlioz’ Romeo and Juliet the realisation dawned once more that without this extraordinary composition and others like it Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde might have remained forever chaste. Two pairs of star-crossed lovers and between them a seismic shift in the evolution of music. Talk about the earth moving.

Rattle’s ability to command our attention and to create atmosphere from that attention was a major feature of the evening. When did we last hear a Prom open in rapt and all-enveloping stillness – a cushion of whispering strings barely moving air, erratic heartbeats caught in the pizzicati of string basses, nine of them ranged across the rear of the orchestra and for now attending only to the music’s excitable pulse. How effectively Berlioz navigates his love scene between tenderness and unfettered ardour and how perceptively Rattle realised not just its warm embraces but also its amazing dying cadences suggestive as they are of those sinking moments where this Romeo and his Juliet feel the cold reality of the approaching dawn.

Tristan and Isolde’s night of love is rather more brutally cut short in act two of Wagner’s opera and here again Rattle’s gripping concert performance sought to prioritise harmonic tension and the music’s other-worldly theatricality. Those brassy period horns sounded at once earthy and cosmic in their dramatic offstage volleys and as Isolde (the marvellously imperious and ringingly secure Violeta Urmana) and Brangäne (the transcendent Sarah Connolly) anxiously acknowledged the timely departure of King Mark’s hunting party a moment of fear descended in barely audible sul ponticello strings and oscillating clarinets as if nature too sensed the fear and folly of the lovers’ illicit tryst. Urmana’s thrilling invocation to the “goddess of love” to bring on the night brought on a feverish eruption from the OAE – and how profoundly that would contrast with the terrible emptiness in the pit of the bass clarinet’s lower register as Franz-Josef Selig’s King Mark movingly chronicled his betrayal.

Unfortunate, then, to once again have to draw attention to the deficiencies of Ben Heppner’s Tristan. The problems that have long beset this fine singer are now so pronounced that the precious timbre and musicality are scant compensation for the distressing insecurities in support and production. Still, Rattle prevailed with a translucent and exalted performance.

You May Also Like

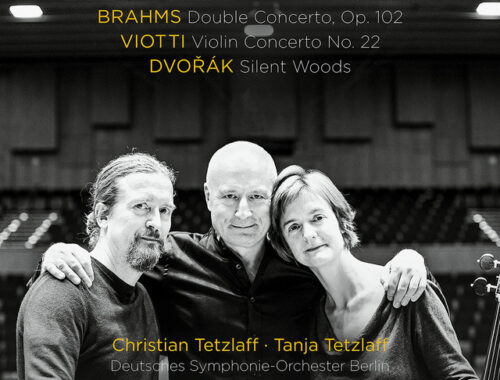

GRAMOPHONE Review: Brahms Double Concerto / Viotti Violin Concerto No 22 / Dvořák Silent Woods – Christian & Tanja Tetzlaff, Deutsches SO Berlin/Järvi

15/12/2023

COMPARING NOTES with ROBERT TRIPOLINO

26/06/2023