THURSDAY 11TH FEBRUARY 2010 PROKOFIEV “THE GAMBLER” ****

Royal Opera House

Like some kind of cosmic roulette wheel Prokofiev’s mighty orchestra starts whirring as the word “Casino” appears, writ large in dozens of flashing bulbs. But Martin Scorsese this is not, nor Las Vegas, but the fictional German spa town of Roulettenbourg where, in Richard Jones’ febrile imagination, it is feeding time at the human zoo. This selection of grotesque, colourfully attired, humanoids are pretty much indistinguishable from the animals unseen inside their cages but for the odd flick of a tail or trunk. But in borrowing the metaphor from opening of Berg/ Wedekind’s Lulu Jones establishes his own menagerie in double quick time. There’s even a performing seal to point up the fatuousness and moral bankruptcy of it all.

Prokofiev’s relentless take on Dostoevsky’s novella is, in short, the perfect vehicle for Jones’ very particular skills. It’s a big, stylised, ensemble piece which turns almost exclusively on a series of compulsive ostinati and like the demon roulette wheel only stops spinning long enough to register the human folly which drives it. Indeed it would be hard to imagine a staging which more successfully replicates the perpetual motion and bold declamatory nature of the score. Jones animates his pathetic parade of caricatures – the cartoon of life – like a master puppeteer. The comings and goings at his Roulettenbourg Hotel – wittily designed by Antony McDonald (circa. 1920s, the time of the opera’s completion) – even suggest an element of schadenfreude as everyone is perpetually eavesdropping on each other’s misfortune. The hungry chorus of affirmation as Alexey appears to have beaten the casino and the system is sung to a kind of robotically synchronised Charleston, a fleeting moment of euphoria before the inevitable crash. Credit will be crunched but for now there’s something to sing and dance about.

This is in many ways a heartlessly sardonic and unforgiving score propelled by the grinding and chugging of Prokofiev’s characteristically machinistic rhythms and Antonio Pappano’s incisive direction. But just when you think that there will be no lyric leavening to ease the unremitting cynicism of it all Prokofiev throws in a moment unexpected pathos that is at once personal and at last real. The scene in which the hitherto indomitable figure of fun Babulenka – the rich aunt on whose inheritance everyone is greedily depending – laments her losses, seems to find Prokofiev, too, in mourning for something irretrievable. Russia, perhaps? It’s a beautiful scene and Susan Bickley took it splendidly.

In such an ensemble piece it’s almost invidious to single out individuals – but one should applaud John Tomlinson’s quivering windbag of a General and Kurt Streit’s suavely malevolent Marquis. Angela Denoke cut a suitably ambiguous figure as Paulina, a women looking to be loved not bought, but it’s a hard voice to warm to and always strikes me more mezzo than soprano with its ample middle and lower registers but foreshortened top.

Robert Sacca (Alexey) has all the top (and the stamina) you could want – and one day will make a splendid Herman in Tchaikovsky’s Queen of Spades – but like Denoke the accented English (a good decision for so wordy a piece) was slightly intrusive. And I can’t help thinking that Jones missed a trick with the final pay-off. No matter – all bets were off long before it came.

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – June 2018

20/06/2018

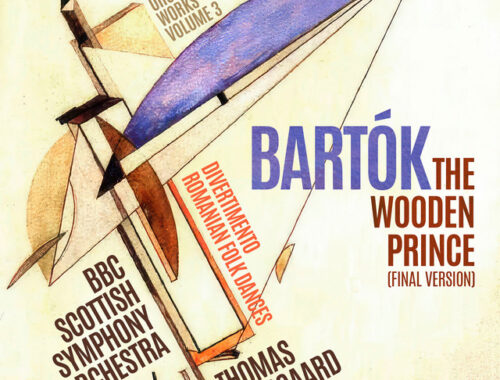

GRAMOPHONE Review: BARTOK The Wooden Prince, Divertimento, Romanian Folk Dances – BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra/Dausgaard

03/06/2024